Legally distinct, as all things should be.

“Mademoiselle? Mademoiselle! A few questions if you will.”

The visibly beleaguered notary struggled to project himself over the stacked books and parchments that, if he’d had his composure, might have lent his too-tall desk an imposing air, an aura of respect befitting his station in the Parisian community. But in this instance, with his client distracted, positioned such that she could–if bothered–simply look at the desk rather than up into it, the notary had to admit that he probably appeared more like a goblin.

“Mademoiselle!” he rasped, a regrettable bit of scorn entering his voice. He was normally much better about his tone with women, but he was behind schedule. He had needed to intervene with the morning’s trouble with the fireplace, and the afternoon had been a nonstop stream of unorthodox contract requests from the sort of clients he had a distinct sense might be hiding something. And this Italian woman, dressed in gender-inappropriate academic regalia, gliding into his office at the very close of business, was very certainly one of them.

“Mademoiselle!” he redoubled, finally prompting a slight, aloof incline of his client’s head. “The collateral arrangement you’ve requested–I’ll need more documentation of these Florentine holdings than–”

“Monsieur Flamel,” the woman said, still not quite turning to face him. “This symbol you have carved into the moulding here–do you know its origin?”

“I’m sorry? What?”

“This symbol.” Her French was passable, though heavily accented. “The cross and serpent. I believe it is occultic, Monsieur.”

She turned, blank-faced, not presenting any clear intent from the otherwise rather threatening question. The woman was not ugly, though her hook nose and mud-brown hair rendered her looks middling by Parisian convention, but otherwise she seemed to sidestep all of his available stereotypes. She was well-past marriageable age, though she had arrived at his office with no chaperone, by all accounts very far from her purported holdings in Florence. She was likely not of noble blood–proof of one’s pedigree was usually the first thing established when an aristocrat requested the notary’s services, and she had provided no such documentation. Or even a claim, for that matter. Whether she was of noble means, though, was the question.

Again, she was very far from home. She must have secured her transport somehow–the notary could scarcely imagine a solitary scholar making the journey all the way from Florence unscathed, much less a solitary woman. But the name she had given–Alighieri–meant nothing to him, and her claim to lands in Florence–to funding, as it all pertained to their business–was unsupported. And she seemed more interested in his office’s walls than her own contractual viability? The notary found his bewilderment and irritation increasing in equal measure.

“Mademoiselle. Your property in Florence is unfit as collateral for your purchase,” he blustered, catching himself in time to qualify: “Without additional dated documentation, of course.”

“Oh, nevermind all of that. I assume gold will suffice as collateral?”

“Um…gold?”

“Two standard ingots and a purse of unmarked medallions, yes.”

“But that would be sufficient to buy the property outright!”

“Oh.” The woman frowned. “Well then, please write the contract to reflect that as payment, if you think Monsieur Menard would accept.”

The notary’s head spun.

“In any case,” the woman continued absentmindedly. “In any case…sorry, how long will the contract take to complete?”

“Um. Three days, most likely,” the notary replied at a mutter. What was going on? That amount of gold thrown about without a second thought at the purchase of a house on Mortelier Street? This was palatial wealth, and this woman wanted to live on Mortelier Street?

“That will suffice. Now, your moulding–I think this is alchemical. Is it not? Are you an alchemist?”

“Mademoiselle!” The notary channeled all the outrage he could muster in his offput state. “I am an ecrivain, a notary, a respectable citizen! And you have come to my office to accuse me of witchcraft?”

The woman blinked, pausing to think, as if a simple rewording might resolve the issue.

“I don’t suppose it would be better to say I am accusing your walls?” she asked.

***

Her choice of words could have been more careful, Dante admitted, proceeding away from Flamel’s office at a brisk walk. She had seen the symbol and gotten excited, and how was she to know that the implications of alchemy in Paris were so…macabre? One might have thought the Church’s taboos against alchemy would have had more force in Florence, closer to Rome as it were–there it was generally regarded as mere eccentricity. But apparently there was more geographic variation in the Church’s influence than she realized.

The conversation had aborted such that Dante was not sure whether Flamel would proceed with her purchase contract or not, which was inconvenient but maybe just as well? The gold which she had volunteered as comparatively unscrutinized collateral was only 20% real. The ingots were genuine, but the coins were just iron that she had plated with a leaf-thin veneer from shaving off the ingots. Were it to be exchanged as tender for purchase, it might well be used, and somewhere along the ensuing chain of commerce, it was very likely to catch up with her. If she’d had her wits about her, she would have waved off Flamel’s comment as to its worth, but she was out of her depth here and struggling to manage the details of her stay in Paris. She’d gotten separated from her manservant back in Milan, and now, given the Black Guelphs had almost certainly seized her property in Florence, all she provably had to her name was a purse of mixed forged and legitimate currency, those two gold ingots, some parchment, ink, and a small collection of personal effects she had been able to carry in her pack out of Italy. For now, she would need to stretch her real money a bit further at the inn.

The meeting with Flamel would perhaps prove not to have been a waste, though. In the shouting match that ensued following Dante’s inquiry into the notary’s architecture, Flamel did provide the indignant defense that his building had been sold to him by an aristocrat with peculiar aesthetic tastes, a “Comte St. Germain”. Flamel was, of course, unhelpful in providing the Count’s current whereabouts and proceeded quickly to a firm request that Dante get the hell out of his office, but she was holding onto hope that this Count St. Germain was still close at hand and–God willing–and alchemist, as his decor suggested.

Dante did not come to Paris prepared to act like an aristocrat. While she was an accomplished poet, that wouldn’t pay for bread. And while she was a mediocre physician, she doubted the French would suffer a foreign woman to minister to them, skill aside. If she could join some sort of venture with another alchemist, though… In her experience, siblings in the Great Work tended to protect their own–and some could even be persuaded to look past their misogyny in the process.

Asking after that name would be tomorrow’s work, though. Now it was getting dark, and she was starting to notice glances, piqued interest from dirty faces in muck-crusted alleyways that she hoped was merely larcenous. She drew from her robes the crudely-sketched map she had made from the innkeeper’s directions to Flamel’s office and attempted to retrace her steps. The cross street in front of her must have been just down the way, extended from the left edge of her drawing. If she could just get a few streets north, then–she glanced up as something stepped between her and the light of the streetlamp she’d been reading by.

Ah, rats.

“Where ya tryin’ to get to, miss?” a rough voice rumbled from the shadow before her.

“You aren’t lost, are ya?” from behind, a few paces.

Dante raised a hand, both to encourage a pause and to dim the backlight so she could make out her prospective assailant. Grubby, thick, crosseyed, black teeth, slightly taller than her–he was hunched over, but so was she–and no doubt quite a bit stronger. He was an obvious cutthroat, of the variety common to every city in Europe, a brainless pair of idle hands with few scruples as to the misfortune of whomever might wander into his cesspool after sunset. Dante assumed the one behind her was identical, since the first was already identical to all the rest she’d ever seen.

“Excusez-moi, gentlemen,” she said, rummaging in her robe’s inside pocket for a small folio. “I assume you’re looking for money, yes?”

“Oh, we’ll accept it,” the ruffian said, smiling greasily, taking a step forward. “For services rendered.” What a disgusting way of putting it.

There. She found the folio, pulled it out, flipped it open–which thankfully slowed the hoodlum’s approach, his piggish face scrunching with misplaced curiosity–and quickly paged through the stack of cut-down parchment squares within.

“Would you say Paris’ soil is more sandy or silty?” she asked, pausing with a square between two fingers.

“Huh? The fuck are you yappin’ about?” the second ruffian muttered. He’d grown closer, which was nervewracking but also convenient. Dante glanced down at the parchment, embellished with an annotated geometric array emphasizing a graduating angular progression of circumscribed triangles. She wasn’t sure it mattered. The array was meant to search, a feature she’d built in to make up for the fact that her geologic measurements tended to be shoddy and low-precision. She drew the parchment from the stack and, as carefully as she dared, dropped it, trying to angle its descent as close to straight down as possible. It fluttered, landing about three feet away, a troublesome lunge.

“Oh, apologies, I’m so very clumsy!” She tried to ham up the useless damsel persona, a role she really did not care for. She often felt useless, of course, but she–true to her father’s delusions–also could not help but bristle against damselhood. She shuffled over to where the parchment fell, which didn’t much give her an angle to run but did coincidentally–and fortuitously–put both thugs on the same side of her. Trying to conceal her excitement–as well as the nervousness at how fucked she would be if this didn’t work–she knelt, reached out, and placed her fingertips on the parchment’s array.

The sensation was immediate, as if a muscle in her mind locked into place, did not merely wait for her to direct it, but rather leeched her intent from context, from her conscious and unconscious thoughts. There was a notion of red flowing from her; the parchment erupted with white light; and the air grew cold. This was literal, in fact: The ambient energy of the surrounding atmosphere, the fire of the streetlamp, body heat from Dante, the thugs, the unfortunate tomcat wandering past the mouth of the alley nearby were all being channeled into vibrations of increasing frequency that her alchemy was directing into the street below. They were powerful vibrations, and when they found resonance with the cobbles and loam, Dante would–via the same transmutative array–delicately pry apart the stones beneath the thugs’ feet, causing the street to collapse beneath them.

In practice, the array locked in on resonance far faster than Danted anticipated, and the street, in apparently poor repair and built over sewer or other unexpected subterranean hollowing, collapsed instantly and explosively with a shrapnel spray of gravel and mud that flung Dante backward, almost fully across the street.

“Hrm,” she grunted quizzically, climbing unsteadily to her feet. The dust was clearing. By the light of the next streetlamp down the way, she could see the jagged hole before the alley opposite her and the unmoving arm protruding upward from it. Fortunately, she also could not see any curious faces in the nearby windows, and she had yet to feel that telltale sense of being watched.

A sensible Florentine woman would have taken this opportunity to run, to put distance between herself and what had become a rather serious act of public vandalism–and likely murder. But a sensible Florentine woman would never have found herself here in the first place. She would never have taken up the serious study of medicine, of geometry, of the natural laws, or of the considerably less natural ones of alchemy. She certainly would not have bought into the ambition foisted upon her that she would be the one to lead her family into a new era of prosperity and nobility, against the grain of her usurer father’s soured reputation. And she never would have led a schismatic faction of anti-papists in an attempt to secure Florentine independence from Rome, earning her exile and condemnation to death should she ever return. A sensible Florentine woman would have ebbed and flowed with the tides of that madness, probably, Dante assumed. And she would never have developed this strange fascination she had found for death.

She crept toward the pit she had made, careful not to approach the arm too quickly, lest it still had that annoying capacity to grasp, and she allowed herself a little grin as she saw the carnage:

One of the thugs had apparently been buried completely, with no part of him still visible. The other, the one whose arm now reached ineffectually for freedom from his chthonic end, still had the better part of his face exposed, a shelf of cobbles embedded into the side of it, leaving little doubt that he was quite dead. It was beautiful, Dante thought, fighting the urge to sketch it on the back of one of her transmutation cards. Absentmindedly, she picked up the remaining torn half of the parchment she’d used to create the pit and stuffed it in her robe. This was just a terrible accident, she thought. Rather: She hoped the guards would conclude. There was no witchcraft involved.

But in truth she could scarcely remove her gaze from the thug’s deathmask. The vision was intensely cathartic, and the salience of alchemy in the course of the man’s end seemed to burn in her brain. This creature was Hell now, a notion of which she was certain, though which her relationship with the Church made electrically complex. Her alchemy had opened the gates of Hell and pulled this man inside. In a world of petty politics, the imprisonments of gender, of failure after failure to break out and rise, was this not a reminder that she still wielded the power of God Himself? And was that not reason for hope?

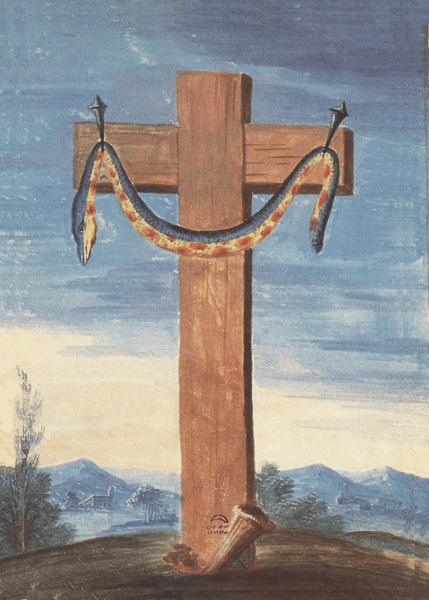

Top image: Emblematic imagery in alchemical manuscripts – Flamel, Bibliotheque Nationale, 18th c.