Ka the Mudfish was known to the people of Mudhull to be a revolting creature. Indeed, this was reflected in his wider reputation: Fishmongers, merchants, tax collectors visiting his marshy domain found him rude. Lords and soldiers of neighboring fiefs harbored deep skepticism as to his administrative competence. Emissaries of the Verdant Tower found him simpering, obsequious, and prone to empty promises. Highlord Michel IV gave him the same attention as the handful of other unsavory strongmen who tended to the periphery of his domain: He did not think about Ka at all.

The fishers of Mudhull, long broken by the Mudfish’s crushing taxes and his enforcers’ brazen thievery, found him a brutal tyrant. And his servants, not permitted residence in his manor and thus compelled to walk between it and their squalid hovels each morning and evening, on roads invariably capped by four inches of oozing muck, somehow found him the most grotesque of all the indignities their serfdom imposed upon them.

Those who respected him were vanishingly few, and there may not have been a single individual alive who liked him.

In this void of regard, then, it was the talk of the village–conducted, of course, in frightened muttering with only the thinnest capacity for interest–when a strange dignitary arrived at the mud-slick steps of Ka’s manor. Some said he was a great general, though perhaps this was rationalized after the fact. Some assumed he was a merchant, though his retinue of stalking, black-clad guards bore no goods. Those who noticed such inconsistencies speculated that he was a traveling scholar, which might not have been wrong, but it was useless, like all the other gossip.

What was clear enough was the man himself: He was tall and thin. His gait was regal and disconcertingly quick. The pall cast by his attention, by his blue-eyed gaze, was frigid, the sort that prompted, as he turned away, the realization that one had been holding their breath the entire time that eye had been upon them. And most salient of all: his other eye, missing, socket uncovered and scarred by a multitude of tiny gouges. Not one of the villagers ever learned his name, so that missing eye served to construct a moniker.

The One-Eyed man entered Lord Ka’s manor that day and spoke with him for hours. Then he and his retinue left. They returned the next day and the day after. That third day, Ka, not given in any sense to generosity, made arrangements that the One-Eyed man, his guards, and the hobbled old woman who traveled with them should stay at the manor. The fifth day, a servant was called into the room where they carried out their mysterious deliberations. The other servants did not see him again, and from then on, turnover at the manor grew unsettlingly high.

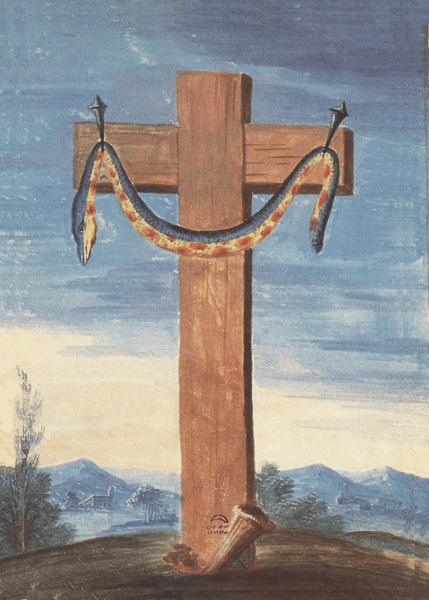

The villagers watched Mudhull’s quiet transformation. Fishers were called from their nets to construct thick wooden ramparts around the village–and long buildings within, laid out like slaughterhouses, though with space far in excess of that demanded by the livestock the villagers kept. Mudhull’s guards donned black armor like that worn by the One-Eyed man’s retinue, now festooned with pewter catfish iconography. The guards’ ranks tripled, with new recruits coming apparently from outlying villages and traveling mercenary companies. And as the quiet transformation swelled into a frantic churn, it was secondary to the villagers when the fishers’ huts began to go empty. In the eyes of history, it is not entirely clear whether their concern even mattered. At that point, it was likely already too late.

It was one day in this rush, this brief window between when Mudhull became inescapable and when the horrors–the roaches and the teeth and the tongues–became clear, that a servant boy was pushed aside in the hall of Lord Ka’s manor by a laughing guard. The boy stumbled, striking his head against the wall as the guard guffawed and continued on his way. The boy remained on the floor a moment, trying to regain his senses, dimly aware that he was bleeding. He wanted to cry out from the shooting pain, but he didn’t dare, for fear the guard would turn around and find his pain interesting.

The boy was ten years old. He had just joined the manor staff, but the few senior servants had exhorted him in no uncertain terms: Keep your head down.

Slowly, the boy became aware of someone looming over him. Shrinking, he peered upward to see a surprisingly short figure, clad in rags.

“Are you scared, child?”

It was an old woman, the one–the boy assumed–the other servants had said arrived with the One-Eyed man. She reached out a gnarled, four-fingered hand and helped the boy to his feet. Her fingernails dug painfully into his skin.

“The fear is a gift,” she said. Half of her face was obscured by her cowl, made darker by the long shadows of Ka’s manor, dim even at midday. Her one visible eye was the color of ice. “Build wings of it and fly away from here.”

She smiled as she spoke, but there was something missing from her tone. Hollowed. Severed.

“Else,” she added, “what else have you to do but abandon hope?”

***

Cirque d’Baton’s attention flickered back to the present as the sun rose over the Crossroads. He saw pale pink creep over the horizon from where he squatted beside a haybale in the alley off Market Street. He heard the telltale birdsong on the other side of the inn’s leaky roof from where he reclined precariously on a shadowed rafter in the storeroom. He heard and saw the town’s complacent denizens greet the dawn across miles, though hundreds of eyes and ears, the more remote accounts–and those he could not be bothered to collate personally–regaled to him in the chittering whispers of the underground. Most of it was uninteresting. Some of it–the townsfolk’s reactionarily privileged obliviousness to their crumbling way of life, for instance–was uninteresting and insulting. But such was reconnaissance. Salience buried in the banal, tactical context within a trash heap of the day-to-day–it was his to sort, and based on the fight Atra had picked, they were going to need any advantage he could pull from it all.

The night had been full of deep breaths and massaged temples. He was irritated with the snags in Atra’s plan, though not so much with her as with the state of the Riverlands. With the fact that there really wasn’t any lower hanging fruit on offer.

The two of them had long since surrendered to the pull of the mana they channeled–him during Mudhull’s grisly transformation before the War, her much earlier–perhaps centuries ago–though Cirque was no historical detective, and Atra never shared that detail. It was magic’s dirty secret, that at some point, inevitably, one would transcend reliance on the power mana conferred: the ability to project death upon the world. Eventually, the profusion of death, the need for mana would become an end in itself. Amateur mages tended to notice the effect, the way that simply being a magical conduit carried a euphoria akin to an owlweed addict getting their fix; but it wasn’t until a mage attempted to really warp the world that the yen of it changed flavor from an easily-resisted chemical suggestion to a gnawing, omnipresent sense of imminent starvation.

And neither Cirque nor Atra had been sated in over a decade. The way that mana became accessible varied for each mage according to their training, their predilections, their memories and traumas–to the ways in which they perceived death. Sometimes, the way Atra explained it, this manifestation was quite straightforward. The fire mage saw death, predictably, in burning. The beastman found it in predation. The sandstalkers of Hazan found it in burial. Other disciplines drew strength from more complex abstractions, like the Grayskins, Khettite diaspora who saw death in the mental unmooring of insanity. Cirque and Atra were both in this latter category.

Cirque was a swarmcaller, a vermin mage, a specialty Atra said had been historically common, though exclusively as self-taught hedge magic–which meant that powerful practitioners were exceedingly rare. In a pinch, Cirque could draw mana in acceptable quantities by simply eating people like a beastman, but it was easier for him to derive death from the slower, more widespread, instinctual depredations of the rats to which he was connected.

Atra, meanwhile, professed to be able to perceive death in war, a theoretically unremarkable claim–except that she said it with respect to the aspects of war distinct from violence: the rage, the distrust, the breakdown of social structure, whatever that meant. The way she told it, this practice was unique in the whole of magical history, which he wasn’t sure he believed, even if he’d seen no counterexample in the fifty odd years they had been traveling together.

In terms of feeding their respective addictions, their partnership had been very effective. Atra’s plans tended to be artful, much more so than the bog-standard False God routine of Show Up, Extort, Slaughter, and Cirque had to admit that he ate better as a town was slowly tearing itself apart than he did in the brief period of gorging after it might counterfactually have been violently pillaged. In return and in service to her social engineering, he lent his capacity as a verminous panopticon. Much easier to play on a place’s internal frictions if you knew what they were saying, everywhere, all the time.

But to that point, the Crossroads was proving an infuriatingly difficult lock to crack. Putting aside the variety of False Gods in its orbit and the three–three!–true gods who were very possibly there too, the town’s cadre of personalities was itself far more capable of resistance than most. It wasn’t the most hostile setup they’d seen: Their run-in with the Hunter of Beasts years ago had handed them their first failure–and Atra her first stinging defeat in combat. But if they pulled this off, it would still be the most impressive feat they had ever accomplished.

The mayor, the actual least of their problems, was far more politically savvy, far more perceptive to intrigue than any of the the yokels they’d had to puppeteer in the past, but if it were just him, Cirque would be sitting back and letting Atra flex her social prowess. However good he was, she was better. But then there were Gene and Brill, old, venerable, level headed and trustworthy, and frustratingly aware of his and Atra’s movements–though their means were not entirely their own merit. Brill in particular was clever, very nearly as savvy as the mayor and much less willing to play their game. Recognized–correctly, Cirque had to admit–that no good would come of it.

And, of course, Marko, fresh off the muttered communications last night about “plans”. His intuition regarding Cirque’s surveillance was, Cirque gathered, most likely a lucky guess. Cirque had been trying to listen in on that theater for over a week now. Sometimes he got snippets, sometimes all the rats could hear through the walls was incoherent murmuring. It wasn’t great, and Marko’s notice was probably just the coincidental accuracy of a broken clock. But the man was a piece of work.

He had cobbled together an admittedly impressive operation on a foundation of paranoia and an altogether bizarre sort of greed that left Cirque puzzled as to why and how the loon had failed to become a False God in his own right. By all accounts, he had the arsenal and the access for it, but he seemed to have a love of money–or of some more abstract form of capital wealth–that held short of maturation into a lust for material power. The result was frustrating. The paranoia made him difficult to assassinate. The absence of menace and the mercantile largesse he brought to town made it difficult to impeach him in the public’s opinion. And his hoard of artifacts then served to undermine Cirque and Atra’s progress, forcing their communication to take place covertly or out of town, tracking him–the Crossroads was the first town to ever notice Cirque’s role in its undoing–and cordoning off spaces like the theater that neither he nor Atra could access.

Those three–Gene, Brill, and Marko–were good sentinels, though with a glaring weakness in their magical know-how that Marko’s wares couldn’t quite make up for, which was what made it feel like such a cruel joke that they were now temporarily accompanied by this bizarre clique of mages. Bleeding Wolf. Naples. Ty Ehsam. And the two god-infected children.

Ty smelled suspicious in a way that likely had nothing to do with his Grayskin-traditional garb. Foul, sickly, bloodsickly, specifically. Cirque had only been to the Westwood once since the Battle of the Ouroboros, but it was a scent that stuck with you. He didn’t like it, even if he wasn’t sure what it implied.

Meanwhile, Naples and Orphelia both seemed practiced in that Grayskin magic that made you unable to trust your senses, though thankfully, Naples seemed to use it more judiciously than the girl, who just last night seemed to plunge the whole tavern into a bout of phantasmagoria by accident.

Bleeding Wolf was probably the most magically attuned of the bunch, and by the way Atra was slavering, he was probably real dangerous in a fight, which made their first-line option for dealing with problematic factors in town that much more fraught.

And Devlin…just…fuck. The smell brought nauseous shivers up from Cirque’s gut. He almost wanted to cut and run, leave Atra to it and just starve or go insane. Hell, part of him was considering suicide before facing the One-Eyed Crow again.

But–deep breath–in truth, every single one of them was a damned problem, and most, if not all of them, understood that they were in some existentially threatening shit, though maybe they didn’t yet recognize that Atra’s plan was existentially threatening itself. For problems like this, the usual solution was pruning, getting rid of individual issues in order to make the rest of the town suitably manipulable. Bluntly: murder.

But as much as Cirque wanted to settle his anxieties, wanted a clear path to the ultimate feast, Atra’s assessment–that the situation was too delicate–was correct. There were too many powerful forces here, and while Cirque and Atra certainly posed no threat to them, escalating violence could very quickly bring the screaming consequences back home. Lan al’Ver would certainly notice a hit on one of his current fixations. This “Ben Gan Shui” had made a deal with the town, and Cirque had the impression she held her trading partners to an exacting standard. He doubted that the Crow or whichever slithering influence had adhered itself to Ty Ehsam would react calmly to attacks against their hosts. And if Atra was right and Orphelia was truly a locus of the Gyre, it was possible that killing her wouldn’t even cause her to die–but would invite retribution nonetheless.

It was maddening. He was multitudes. He was untouchable, inexorable, and omnipresent. Cirque had transcended the humanity that imprisoned him in Mudhull to become what was practically a demigod to these insects, and he still felt helpless.

Atra thought she still had this, confident she could steer this happy, “rebuilding” hub of trade into a well-armed but ragged and duplicitous alliance with Holme, all in service to a last stand against the Blaze. The Crossroads would be decimated, Holme would be destroyed. The Blaze’s army of mutants would be slaughtered. Atra still somehow saw the path this great conflagration, snatching the flocks of two False Gods right out from under them, and all Cirque could do was hope she was right–and continue to make sure she knew everything about the way these animals danced.