Lan al’Ver awoke with an uncharacteristic jolt. It was becoming more frequent. Sleep. Dreams. The writhing and resonance of the Night Sky’s mind was intruding ever more upon the world’s substance. Structure was beginning to decalcify, mana ran rich with dreamsilt, and even beings such as Lan, who had long since dispensed with the biological necessity of somnolence, were having it thrust upon them. Unimpeded, the end would be here soon. Perhaps in weeks, perhaps in years, but when He woke up, reality would melt into dream, and dream would melt into nothing. Only the Dark would remain, and that was lovely for the Dark, but Lan was beginning to view the prospect of nonexistence with a new apprehension of late. Perhaps the Alchemist had been right. It was fortunate the man had been so persuasive during his crossing.

Lan surveyed his crowded raft. Dawn had not quite arrived, and the sky was still a deep, whorled grey. The others were still asleep: Orphelia and Devlin huddled inside the raft’s small cabin, Ty Ehsam the scavenger crouched against its outer wall, and Naples the scholar lounged, snoring, atop a pallet of linen bolts. None, apparently, had noticed his lapse in vigilance. And he had woken before they had come upon their intermediary destination, so it seemed no evidence remained for them to find. All was still in hand so far, though the uncertainty of it chilled him.

A soft breeze blew through the reeds, the minutes passed, the sky lightened, and as his companions began to stir, Lan maneuvered the raft to the bank, just as it began to widen before them.

Seek the Keystone, and bring it to the shrine where once you ruled, Excelsis had said. Though he was still unaware of the purpose of this errand, Ty had the Keystone now. They had gone to some lengths to extricate it from Les Marquains’ clutches. He would certainly be disappointed to learn he would not be handing the stone over to the Blaze, but the stakes were higher than he could know. Even if he saved himself from the fire, taking any other course would end him–and everything–all the same.

“The shrine” where once Lan “ruled” was a flattering reference, even if it was based in historical inaccuracy. Lan’s erstwhile incarnation, the “Turtle on the River’s Surface”, as the remaining stories recalled him, had never been a political entity, much less a ruler. But nonetheless, for a time, there were some humans who claimed him as a guardian. Those humans, the ones who charted and spread across the Riverlands, who became, in fact, the first Riverlanders, maintained among their disparate tribes a place of confluence here, at the fork between the Lifeline and the Artery. Over time, its permanence in culture became permanence in edifice, and as the Turtle–the creature–faded into the background, the turtle as a symbol rose in the form of the Godshell Palace at the center of the floating city of Thago, capital of the Revián Federation.

It had been many centuries now since Thago had been destroyed, torn apart by social unrest and an opportune attack by the Diarchy of Spar, their rival to the east. Though Lan had felt the loss of Thago keenly at the time, he had grown to understand that by then, the age of the Old Gods had long since ended. Thago had all but forgotten him, palaces notwithstanding, and Spar had almost certainly forgotten Brother. It had become a world of men, of their creation, and Lan’s role from then on was merely to live in it. There were worse fates. Though now it seemed had one last debt to pay the world he no longer guarded.

Now at the fork in the river where Thago once floated, there was nothing left, not even ruins, save perhaps some disintegrated hull fragments long stuck in mud and shielded from the eroding currents. But Lan was reasonably sure it was the place which was symbolic in the Alchemist’s gesture and not the literal architecture. No, he presumed–and his presumptions were generally apt–that what he was looking for here would be the Alchemist’s creation.

“Did you stop to rest, al’Ver?” Ty asked. He had stirred, it seemed, awakened by their cessation of movement.

“Captain al’Ver,” Lan corrected, though not disdainfully. Ty was attempting well enough to blunt his own discomfort at their decreased pace.

“Yes, of course. Captain. But–”

“No, Mr. Ehsam. We have stopped because there is something the two of us need to see.”

“The…two of us?” The question was punctuated by a moist thud as Naples toppled to the deck.

“Wha–what’s all this?” the scholar asked blearily.

“No need to worry,” Lan assured. “Please keep watch over the children. We will not be away long.”

With that, he stepped out onto the bank, Ty bewildered but in tow. The reeds were thick where he had moored the raft, and if there were anything hiding in the mud near them, it would be all but impossible to find. But Lan doubted it would be so close to the river’s churn. Excelsis, whose life’s work had been toward the preservation of the world, would have been particularly wary of erosive influences. Up ahead, there was an outcropping of rocks which would certainly be a more fruitful ground for their search. Lan drifted up the uneven terrain on footholds he suspected were too slight for Ty to notice as Ty, accordingly, ignored them, clambering up the rocks with impressive agility but no small effort.

“Al’Ver. Captain,” he said, about three quarters of the way up. He was trying to disguise his heavy breathing, only mostly successfully. “What are we doing here?”

“We are looking for something the Alchemist left us, Mr. Ehsam.” Ty’s frown deepened to incredulity.

“What? No! Absolutely not!”

Lan peered between a gap in two boulders, spotting the telltale contours of stairs hewn into the rock.

“Right here, I believe,” he said. Ty looked through the gap.

“Oh, gods, there’s actually something here,” he muttered. Then, more dedicatedly: “No! I’m done with this, al’Ver! I finally have my freedom in hand, and I’m not going to risk it for a payday on whatever manse or lair this is. I need to get back up north!” He turned to leave, but Lan called after him:

“It is precisely because you have the Keystone that we are here.” Ty stopped, looking back at Lan with sudden suspicion. “Did you think your quest was merely coincident to my journey to the Reach?”

“I did,” Ty said slowly, eyes widening with something approaching recognition. “What does this have to do with the Keystone?”

“Some time ago, the Alchemist asked me to find it and bring it here. I have done so. Now we must see what that was meant to accomplish.” Ty stared.

“The Alchemist died nearly a century ago,” he said. “Who–what are you?” Lan held his gaze for a moment and then turned back to the occluded staircase. He began making his way downward. Ty would follow in a moment. He was resistant, but the stream had him now.

At the bottom of the staircase, surrounded on all sides by rocky walls made more of intentionally-placed stone bricks than the random boulders above, Lan paused before a metallic door. It was peculiar–dark, almost black, not iron or steel, nor any other metal with which he was familiar, though metal was hardly a domain over which he claimed expertise. He waited to hear Ty’s dampened footsteps behind him before opening it, stepping out of the way of the corpse that fell into the doorway.

“Fuck!” Ty hissed.

The corpse was practically mummified, its skin taut and pale-brown over its bones, though its chest had been flattened, with a large, square crater of pulverized flesh and bone in the center of its otherwise-preserved torso. It meant they weren’t the first to find this place, though they were likely the first in some time. It also meant something else, though Lan trusted Ty’s instincts were sharp enough for him to discern it on his own. He stepped around the corpse and into the large, rectangular room beyond.

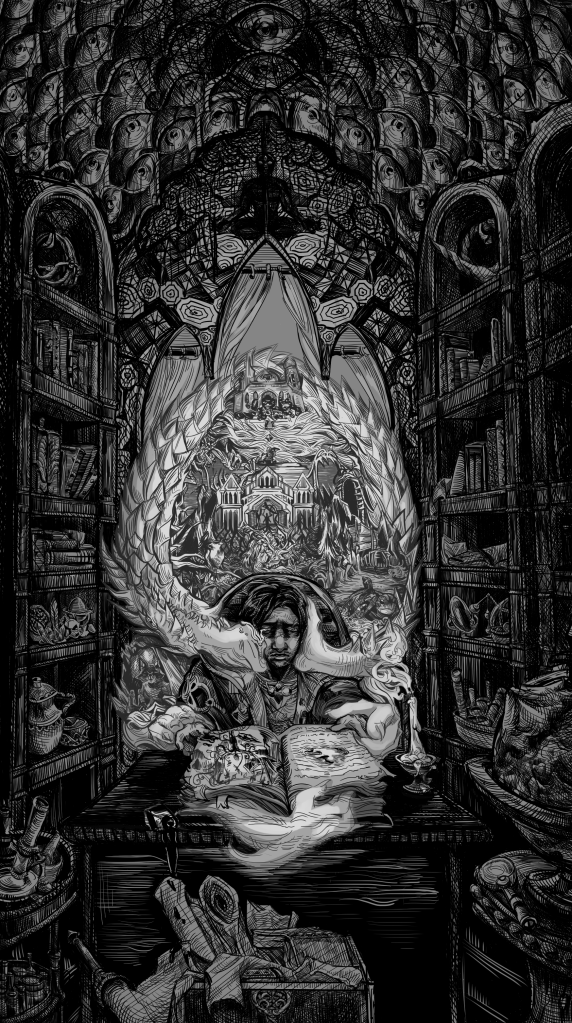

As he did, a number of crevices at the base of each wall came to life with a green glow, illuminating a dizzying array of symbols etched into nearly every inch of the stone walls, floor, and ceiling inside. Lan was no metamage. These symbols were neither within his command nor comprehension, but he was not blind to the ways that humans interacted with the residual dream and death they called “mana”. Even if he did not know what they meant, he knew what they were: mathematics, epistemological declarations alien to his own experiential nature, memos to reality as to the specifics of the transmutations the mana was meant to invoke. The entire room was an artifact, then, but on the off chance an entrant knew the language the Alchemist used to document his enchantment, they might glean some idea of his intent. Fortunately–or unfortunately, as may have been the case for their semi-embalmed forerunner–it seemed Excelsis had left a separate message in a more universally understood language, and that message began to rumble to life, separating itself from the wall as Ty tiptoed in, and the door behind them squealed shut.

It was a golem, a magical constructed wielded by earth mages the world over, its anatomy sculpted to a crude humanoid shape in the same cubic bricks that made up the rest of the room’s surfaces. This one was unique, however, in that the evocation of a golem was a somewhat demanding allocation of mana, and this one seemed to be persisting in the absence of a mage.

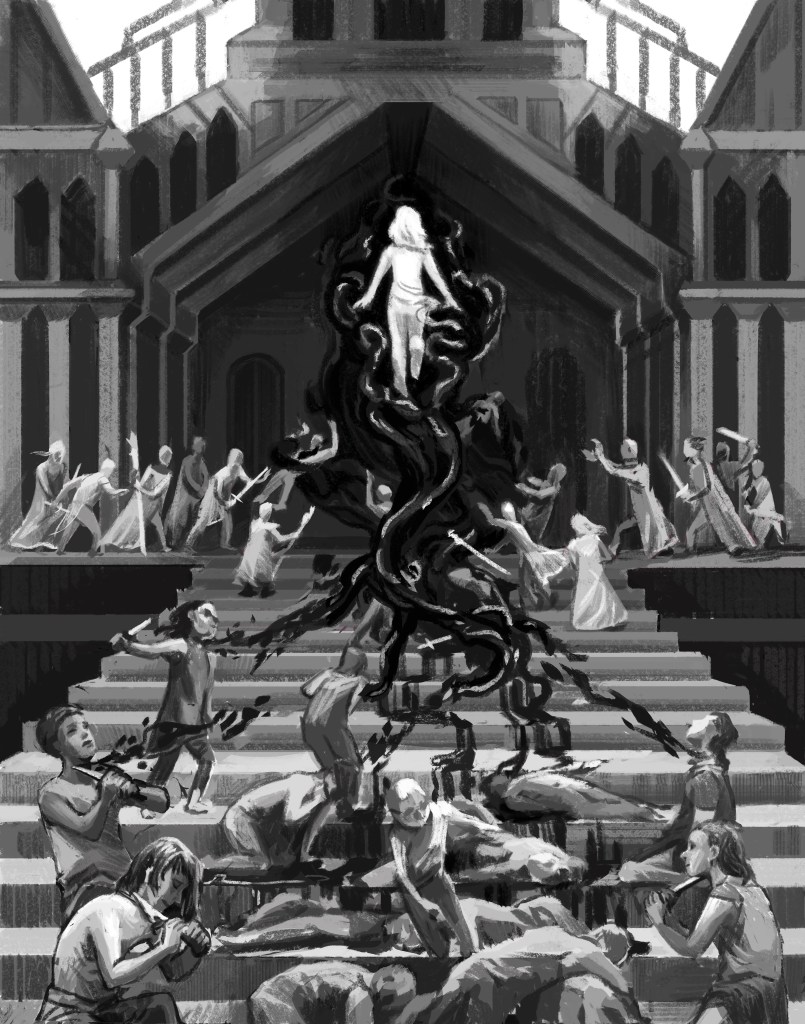

“Ready the Keystone, Mr. Ehsam,” Lan said. The golem braced to charge, its intent–to the extent an unthinking construct’s will to violence might be considered intent–eminently clear.

“Ready it for wha–gah!” Ty threw himself sideways as the golem lurched into the spot where head had been standing, coming to a halt with the force of a rockslide but far more grace than its unwieldy form might have implied possible. Lan swatted at its “head”–a gesture which had little hope of impeding it but which might acquire its attention. The ploy was partially successful: The construct’s torso spit around the axis of its waist, causing its arms to whip outward at the men on either side of it, stretching–in such a way that the bricks in its arms separated from each other slightly, held together by nothing but pure mana–and clipping Ty, sending him reeling back into the wall.

“The Keystone was to be brought here,” Lan said, keeping most signs of concern from his voice as he leaned out of the way of the golem’s whirling strike. “We must find what it was to be brought to.”

“Oh, must we?!” Ty snarled, pushing himself upright and dashing away from the golem. Amidst the chaos, it seemed he had, in fact, followed Lan’s instructions: The marbled blue medallion was dangling by its chain from his fingertips.

Lan regripped his umbrella and drove it more dedicatedly into the construct’s cranium, with force that likely would have broken a human’s skull. Almost surprisingly, the surface gave slightly against the blow. Reasonable, he supposed: So mobile a configuration of stones might not be the most stable one. Either way, it seemed he had its attention.

The golem shifted its strategy, squaring up toward Lan and seeming almost to widen. It had learned quickly, he realized. It had gathered that its sudden movements were not sufficient to surprise him, so now it meant to corner him instead. Slowly, it began to stretch an arm toward him. Excellent. He had been hoping to see whether this would work. As the stones in its arm once again began to separate, he jammed his umbrella into one of the gaps and levered it hard.

Golems, in his experience, were not difficult to partially destroy. All one had to do was overpower the local mana the mage was channeling to hold a particular piece together, which, for the joints, was generally not very much. This was only so useful in the normal case, though, since a mage would be able to regather whatever was destroyed in seconds. Lan was curious, though, whether Excelsis’ guardian possessed the wherewithal to repair itself. Sure enough, its arm shattered at the elbow, the stones falling uselessly at Lan’s feet, but the construct did not give him the pleasure of confusion at its sudden disarmament. It simply rushed him.

He opened his reinforced umbrella in an attempt to blunt the impact, though he doubted how much it would matter in preventing his imminent flattening against the wall. In the end, though, he did not find out. Nor did he answer his question regarding the construct’s regenerative talents. As it impacted his umbrella, the golem’s entire body disintegrated into rubble, which washed over him uncomfortably but harmlessly. Simultaneously, every inscrutable symbol on every wall lit up with the same green glow that lined the floor. Lan looked to Ty, standing at the opposite end of the room before a large, stone slab. At the center of the slab, slotted into an indentation and glowing a brilliant blow, was the Keystone. The door they had entered by swung open.

“Ah, so there is something he–ah, Captain! There you are!”

Naples poked his head into the room, flanked by Orphelia’s diminutive form. Lan fixed him with a disapproving glare.

“I instructed you to keep watch over my vessel, Mr. Naples,” he said, picking pebbles from his glove.

“I’m afraid you merely instructed me to keep watch over the children,” Naples replied, attention suddenly overtaken by the glowing room. “And they are, uh, here, of course.”

“Ooh, what’s this place, Captain?” Orphelia asked, following him in, dragging Devlin, semiconscious, by the wrist.

“A place of not trivial danger, my dear,” Lan said. He turned his attention to Ty, who was trying to make sense of the slab which now bore the Keystone–and from which, to his mounting frustration, he seemed unable to extricate it.

“Danger is fun,” Orphelia probed, picking up one of the golem’s fragments, not entirely convinced.

“Is this one of the Alchemist’s laboratories?” Naples asked, breathless.

“You call this a laboratory?” Ty shouted over his shoulder, trying to get a grip on the Keystone, to no avail.

“I suppose not, but…these are most certainly his runes. I’m sure of it.”

“You can read the Alchemist’s language, Mr. Naples?” Lan asked, bemused.

“Not well, not well, but Master Jabez taught me a little. Like–” he gestured to the indentation where the golem had separated from the wall. “This seems to be describing a ‘doorman’ who turns away anyone without an…’opener’. Or, yes, a key! So it would…” He glanced from the slab and Ty over to the pile of rubble. “Perhaps you’ve already gotten that far.”

“You wanna make yourself useful?” Ty snapped. “Come tell me what all this shit means!” Cautiously, Naples approached with Orphelia in tow as Devlin took a seat amidst the scattered stones.

“So this is less verb-y…lots of relative and reflexive particles I don’t really follow, but the two biggest pieces are here–” he tapped a series of large runes at the bottom of the slab, “–which is a compound of ‘fire’ and ‘gathering’ and ‘place’. I’d maybe translate it as ‘hearth’ or ‘campfire’, not sure about the context.” He pointed up at a similarly-sized inscription at the top of the slab. “And that’s…that’s weird. The rune in the middle means ‘within’, but the ones on either side aren’t really standard as far as I’m aware. That one on the left looks sort of like ‘dream’, but also like ‘night’, or even ‘mage’, which is itself a known modification of ‘death’, just with an indicator to denote it is being wielded.”

Ty exhaled, clearly apathetic to the nuance, but he held his tongue. Lan, for his part, was intrigued. It was a rare occurrence that he should encounter something he was so thoroughly unaware of, and he was happy for Naples’ aid in the discovery. Moreover, he had heard the name Jabez Faisal before, upon tertiary currents. Perhaps he would need to make a point of meeting this individual.

“And the one on the right appears to be a fusion also. I see the distinctive marks of ‘human’ and ‘tool’ and ‘small creature’ and…’asleep’?”

“What does it mean?” Ty blurted, his frustration finally boiling over.

“I, uh,” Naples stammered. “It means ‘dream-night-mage within asleep-small-human-tool’. Beyond that, your interpretation is as good as mine.” Ty grunted, punching the wall with his palm.

“All that fucking knowledge, and even you don’t know what to do with this? Dammit!”

Lan laughed.

“Mr. Ehsam!” he said. “That was your question? I’d thought you might spare the moment for a fascinating lesson in linguistics, the way forward being as obvious as it is.”

“Obvious, al’Ver?” Ty asked through his teeth.

“But of course! You brought the Keystone to the door. All that’s left is to open it!”

With that, Lan grasped the right side of the slab and pulled. With some resistance, it swung open, the Keystone receding into the indentation where Ty had placed it.

Inside, half-embedded into the wall, was something that looked like a man but was not. Rather, Lan noted with interest, it had a man’s face, cast meticulously and realistically in silver. Its limbs, he supposed, while anatomically correct enough, were far too runed, metallic, interspersed with filigree and empty space for any observer to realistically mistake them for human flesh. It was, all told, a beautiful sculpture, but more pertinently, it seemed that the Keystone, through the door, had connected with a slot on its chest, where it now rested, pulsing a soft blue. Then, as if in answer to all of their questions, the sculpture opened its black eyes.

“I am awake,” it said. Its voice was human enough, vaguely male, though it sounded as if it were echoing through a hallway made of tin. “Please confirm the status of the scenario.”

“…what?” Ty breathed, incredulous. The sculpture’s head turned very slightly to face him, though the rest of it remained perfectly still.

“Very well,” it replied. “I will clarify the scenario subpoints: Is Excelsis dead?”

“Yes?” Ty said skeptically, taking a reflexive step back.

“Thank you. Is the Night Sky’s awakening imminent?”

“What?” Ty muttered, but Lan supplied the appropriate response.

“It is.” All eyes turned to him, including the sculpture’s.

“Thank you,” it repeated. “Is the place of His awakening known to you?” Lan frowned.

“I’m afraid not,” he said.

“Very well. Is the Great Fire nearby?” Ty squinted.

“The Great Fire?” he asked. “The Blaze?”

“It is not,” Lan clarified. “Though it approaches from afar.”

“Thank you,” the sculpture replied. “The status of the scenario is currently viable, provided the Great Fire remains ambulatory. It is my recommendation that the place of awakening be located immediately. I will aid you in this effort, to the best of my ability.”

With this, the sculpture’s limbs came to life, and it began to climb down from the wall. Its motions were not graceful. It stumbled slightly upon touching the floor, but it righted itself quickly enough.

“No, no, no, no,” Ty sputtered, moving to intercept it. “This isn’t–fuck!” As if struck by an unseen force, he reeled backward, clutching his temples. “This wasn’t the deal!” The motions of Ty’s mouth in the following sentence were slurred with hisses and grunts of pain, but Lan caught the quiet, whispered response that he knew was not really from Ty:

“This was exactly the deal,” he said.

“Are you alright?” Naples shouted, running over to Ty while keeping a wary eye on the sculpture, who merely watched impassively.

“That was my out!” Ty shouted. “That stone was gonna save my life!” He sank to his knees, in defiance of Naples’ efforts to help him up.

“Quit your whining,” Lan said, adopting a haughty sternness. “Now it will save everyone’s life. Ideally including your own. Now construct–what may we call you?” Once again turning to face Lan with an uncanny minimum of movement, the sculpture replied:

“I…was designated the title Homunculus.”

“Very well, Homunculus, are you able to explain the remaining steps of this ‘scenario’? Excelsis declined to provide the particulars.”

“Yes,” the Homunculus replied. “The objective is to bring the Great Fire into confluence with the Night Sky’s awakening, for it is fire which wards off the night.”

“Yes, yes, the business with the scarab and the broken nose,” Lan said. “Are we to get our noses broken too? Then off to sleep with Father again?”

“What?” The response came asynchronously from Ty, Naples, and Orphelia, though the Homunculus’ was much the same:

“I’m afraid I do not understand,” it said. “But to the broader context, I cannot say what the precise impact of accomplishing our task will be, merely that it should forestall the erosion of reality. To that end, it is ideal that the confluence with the Great Fire should be both spatial and temporal, though I am equipped to correct for errors on either side, provided we locate the place of the awakening.” Lan nodded, planting his umbrella on the floor, satisfied.

“Excellent, then. Please join us, Mr. Homunculus. We have a lengthy journey yet.”

“Al’Ver!” Ty hissed, climbing to his feet. “Enough with the sweeping us all off to adventure. What the hell is going on?”

“Put simply, Mr. Ehsam, the substance of the very world has been on the brink of dispersion for some time. This world was created, its creator is not inclined to keep it that way, and it was the Alchemist’s last wish that something be done about all that.”

“Do you have an idea where this ‘place of awakening’ is then, Captain?” Naples asked, playing along reticently but admirably.

“Not even the faintest,” Lan replied. “But I’m sure we’ll find it by some road. And around here, all roads lead to the same place.”