A review of Embassytown, by China Mieville.

Circumstances being what they are (ie, needing to focus on finishing one more manuscript while I have the freedom to do so), it is likely that the following will not do China Mieville’s Embassytown justice. Perhaps that’s because the book is a lot, perhaps it’s because it’s just a lot that I’m personally interested in. It’s become depressingly clear to me over my adult life that the average person just cannot be persuaded to care about epistemology. That’s fine; it’s a headache, but just as others may enjoy headaches in the form of booze or boxing, the nuances of knowing things is a headache that speaks to me. And boy oh boy does Embassytown speak that Language.

Cheap pun notwithstanding, this book is silty. It’s classic Mieville, which is to say it’s not especially forthcoming with what it’s about, despite seeming to follow a cogent narrative arc. I’m not sure why this is so common in his work, since it seems to be a different sin (or at least a different purpose) depending on the story you’re reading. In Perdido Street Station, it’s an issue the setting gobbling up pages in exploration of details and implications extraneous to–and thus obfuscating–the plot. Meanwhile, in Kraken, it’s just an excessive amount of intentional misdirection (seriously: That book builds to a climax around the theft of an idol worshipped by a squid cult, only to reveal that the god-squid was merely incidental to the antagonist’s quest to become a god of ink, which is then thwarted by the protagonist’s realization that he has become a god of glass containers, only then to reveal that the apocalypse he was seeking to avert has nothing to do with that antagonist’s scheme and everything to do with the ideological impact of Darwin’s theory of evolution, completely unrelated to squid, ink, or bottles).

Embassytown is somewhere in between. The setting is, of course, very whacky, and a lot of space is given to implications and interactions of its aspects, but after the third (or so) major paradigm shift that changes how everything operates, one can’t help but feel a little jerked around. To that end, I think it’s fair to say that as a story, the pacing is kinda flawed. It’s still gripping, in ways, for reasons, but what makes the book great is what it is beyond a plot.

For starters, like most of the sci-fi genre, Embassytown is about its premise just as much as the series of events that occurs within it. That premise is that there is a planet on the edge of known, navigable space that is home to a sentient species (the Ariekei; the planet is Arieke) that can communicate only via the weirdest language. They have two speaking mouths, and each word or term is constructed of two words, spoken simultaneously by those two mouths. No, that isn’t the weird part. The weird part is that they are incapable of registering anything not spoken in this language, according to particular constraints (cumulatively, Language) as communication at all. A person speaking to them in a foreign tongue; body language; writing–they are aware that there is a thing moving or making sounds in their vicinity, but they will not, cannot understand it or even grasp the notion that there might be thought or intent behind it. Even weirder, when two people repeat the phonemes of their Language back to them, down to the precise pronunciation and simultaneity, the result is the same: They don’t react. It isn’t communication to them. Only through a slow, historical stumble (which the book briefly summarizes) do the linguists making contact figure out that the two halves of Language must essentially be spoken simultaneously by a single mind in order to be comprehensible.

This discovery prompts a series of attempts at workarounds. Mechanical aids (to provide the second speaking mouth) don’t work, ditto synthesized sounds in general. The closest of the first drafts is identical twins, which mostly doesn’t work either, but per Miracle Max, mostly failure is slightly success. Humans devise psychological tests to evaluate empathic synchronicity, gather the sets of twins who score the highest, and then further augment that synchronicity with cybernetic implants. This works okay, and they are able to establish basic lines of communication with the Ariekei. By the time of the book’s events, though, this is all rickety, ancient history, and the embassy (of the interplanetary empire that originally made contact) has moved onto using precisely-engineered clones. These are the Ambassadors.

A brief digression: Some portion of the book gets into the significance of Arieke to interplanetary politics, which is amusing anticlimax. The planet is, in fact, very valuable, but for reasons that have nothing to do with natural resources, the oddities of Language, or the super weird, biorigged technology in which the Ariekei specialize. So going in, the score is that the interests of the empire and its embassy only slightly intersect. Contact with the empire is of a fraught sort of salience, but it’s infrequent. Embassytown (the place, not the book) is out in the boonies, and the way in which its citizens have gone (or proceed to go) native is part of the point.

Anyway, the Ambassadors communicate reliably, but the way the Ariekei work is still a bit opaque. For the Ambassadors, speaking Language requires a lot of engineering, but in the end, Language for them is just language, a semiotic construct. For the Ariekei, it’s not. For them, Language is Truth. They can’t lie, for instance, but it is more than a preventative for deception. They cannot describe anything they know to be contrary to reality, they cannot speculate as to anything that has not happened (they have a future tense, but it can only be used in situations of extremely high certainty), they can’t use conditional hypotheticals or metaphors, cannot even conceive of them. In order to access new concepts, they have a practice called “performing simile”, in which an individual, frequently a foreigner from Embassytown, performs some task of abstract significance under ritualistic observation. These individuals, including Avice, Embassytown’s protagonist-narrator (her simile, roughly translated: “the girl who was hurt in the dark and ate what was given to her”) effectively comprise the Ariekei’s limited window into that which is not.

Needless to say, this is all very bizarre, but the embassy is not especially interested in understanding the boundaries of these limitations. They don’t want to rock the boat–the status quo is awesome for them. They effectively rule their provincial kingdom, coexisting peacefully with the Ariekei via their genetically-engineered, diplomatic metis. For one, elucidating the fundamentals of their diplomacy undermines their interests: The empire understanding what they do makes them replaceable. But also, they would honestly rather the Ariekei not discover anything wild and crazy in their linguistic differences, lest the embassy become a victim of a cultural revolution that turns political. Of course, this is exactly what happens.

Actually, that isn’t precise. It’s what almost happens. And then it’s what happens so hard that nothing will ever be the same again.

The book’s first conflict is fairly organic. Per the above, despite their best efforts, the embassy has introduced a new, invasive oddity into Ariekei culture: The Ambassadors can lie. It turns out the Ariekei have noticed and find it very interesting. For many, it’s entertainment, something between a magic show and a freak show, but a group–of what Avice speculates are sort of Ariekei intellectuals–pick up the idea with more curiosity and attempt to learn how to lie themselves. They can do it, sort of. With great difficulty, by omitting words from sentences, by tricking themselves into failing to finish thoughts, they are capable of vocalizing things which they know to be false.

But they don’t stop there. The intellectual clique, led by an Ariekes named Surl/Tesh-echer (each side of the slash said simultaneously) appears to be fixating on a group of human similes as a means to speak falsehood without having to trick oneself. Ultimately, Surl/Tesh-echer is able to say, in front of a crowd:

“Before the humans came we did not speak so much of certain things. Before the humans came we did not speak so much. Before the humans came we did not speak.”

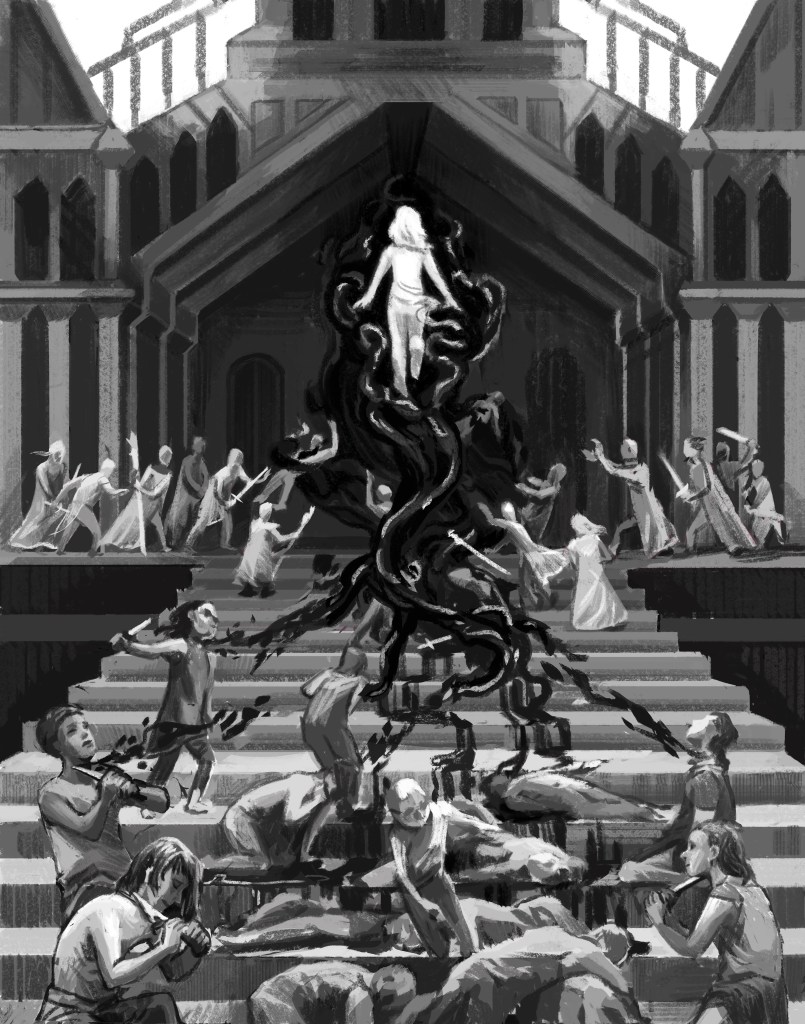

And then, in very short order, Surl/Tesh-echer is assassinated in a conspiracy between the embassy and the Ariekei “rulers”. Everyone agreed, apparently, that it (Ariekei use impersonal pronouns, or the Ambassadors do for them anyway) was onto something, and none of them wanted to find out what, for reasons ranging from brutal realpolitik to religious fanaticism. The book presents this arc, effectively the first, post-prologue, interspersed with the events leading up to the true crisis years later, and from a storytelling perspective, it is Embassytown at its (and Mieville at his) best. It’s an elegant introduction to a highly complicated world and a heartbreaking belated coming-of-age for Avice, who had somewhat intimate personal connections to both sides of the assassination conspiracy. This isn’t to say that the two thirds of the book that follow are a letdown–the beginning merely stands very well on its own. What happens after, though, is where the already philosophically heavy situation gets spicy.

So: Several “years” later (time spans that large are measured in the book in kilohours, because space), the empire sends an Ambassador to Embassytown. This is, on its face, already strange. Ambassadors don’t come from the empire–they are grown in a vat in Embassytown (an ethically spiky topic on which the book touches but does not dwell). Moreover, the particulars of the empire’s Ambassador are highly atypical. Again, modern Ambassadors are sets of doppels, perfect clones, cybernetically linked and physically re-synchronized (so that minute differences in their physical experiences do not accumulate) on a daily basis. The empire’s new Ambassador, EzRa (this is the ambassadorial naming convention, e.g. BrenDan, JoaQuin, MagDa, JasMin) on the other hand, is just two completely different guys with a supposedly off-the-charts score on the paired empathy test that predicts ability to speak Language.

But can they speak Language? Ha. Haha. Yes, but really badly. This is not “badly” as in “their grammar is terrible” or “they are hard to understand”. Rather, when they speak, it enraptures the Ariekei into a trance. It takes a minute for anyone to figure out what’s going on because, surprise, this isn’t what the empire intended at all. They knew their new Ambassador was scientifically fucky (there is, of course, more going on technologically than two guys who just really get each other), but they were genuinely just hoping to create a pipeline for Language speakers they could control. Within a few days, the embassy is able to put enough pieces together to relate EzRa’s oratory to a little known phenomenon they had encountered in their own failed Ambassadors (of which they apparently have an asylum-full in the basement). Turns out that when a pair of humans speaks Language in a way that is just slightly off, the effect on the Ariekei is not distortionary but narcotic. In a small way, the Ariekei can become addicted to the infinitesimal incongruities in a miscalibrated Ambassador’s voice. Except what’s going on with EzRa is not small. The high of their voice is potent enough to spread demand like wildfire: Upon their first public pronouncement, the Ariekei subsequently flood the embassy, overcome by fervid desire to hear EzRa’s voice based on nothing but word of mouth. And once they hear it, the addiction does not seem to have a cure. If an Ariekes goes too long without hearing EzRa say something else (and it has to be something new–repeated pronouncements induce tolerance rapidly), they just shut down.

Oh, but it gets worse.

Virtually all Ariekei infrastructure is biorigged, organic, chemically and physiologically interconnected, which means it isn’t just the Ariekei individuals who are addicted. It’s every Ariekei machine, vehicle, and building on the planet as well. Embassytown is still mostly human architecture, so it isn’t entirely a biological construct, but it isn’t unaffected. The most visible clock to emerge from this development is that the addiction afflicts the aeoli used to convert Arieke’s toxic atmosphere into human-breathable air, which means that unless the situation is stabilized, everyone is gonna die.

It gets even worse than that. And then, it gets even worse than that. In summary, everyone loses their shit; Ez murders Ra; the embassy, in whose leadership Avice is taking on an increasingly active role, figures out how to “replace” Ra in order to keep the Ariekei going and creates EzCal, who is way too into his role as the “god-drug” and begins solidifying power structures around himself; the Ariekei begin to deafen themselves in order to cure their addiction (which, for a species for whom spoken language is thought and unspoken language isn’t language at all, is way worse than it sounds); the deafened Ariekei begin massing an unstoppable horde, hell-bent on the extermination of the humans and addicted alike; and Avice goes renegade and discovers a way to teach the Ariekei to use referential language, which cures the addiction and stops the forthcoming genocide. I want to be clear that my description does not do this last step justice. It is extremely awesome, and I would almost recommend reading the book just for that portion of it.

Needless to say, this is all extremely analyzable. The low-hanging fruit, the piece that I imagine a socially-involved but not especially careful reader might notice with immediate umbridge, is the commentary on colonialism. Embassytown as a colonial story runs counter to the anti-imperialist narrative in vogue right now, and without getting too political, I do want to clarify that that narrative has a lot of good sense behind it: Historical colonialism was rife with utter atrocity, and it is hard to defend the intent behind it as any more noble. This is why my above weakman would not be wrong to be immediately suspicious of Embassytown’s characterization of its colony as native-friendly. Anyone even passingly familiar with the concept of bias should immediately recognize that first-person good intentions are very easy to presuppose and wildly difficult to ethically execute on. But counterpoint: This is fiction, not a geopolitical instruction manual. Mieville is at liberty to define whatever setup he wants, without any obligation to make that setup replicable in real life, and the setup he defines is one where the colonists have little power over the natives, and their empire has little interest in establishing any direct political control. Part of this should be understood as a change in economic theory between now (and especially Mieville’s stellar far-future) and the 15th century, largely independent of the parallel shift in geopolitical ethics (it is worth noting that despite Mieville’s impressive authorial catalog, he also has a fair amount of training in law and economics). A little-appreciated observation is that mercantilism as a driving motivation for early colonialism was catastrophically destructive for the places getting colonized, and Embassytown is operating on very different sensibilities. Specifically, the empire in the book is operating with the specific interest of being friends with whatever human settlement ends up on Arieke in the long run. They don’t really care about conventional exploitation (though they do want reliable and semi-exclusive diplomatic influence), they certainly don’t want to be financially responsible for the settlement’s survival. And the resources? Meh. Biorigging is neat but probably not a game changer. No, the value for the empire is deep space exploration, and Arieke is the farthest outpost available. They just want to be on better terms with that outpost than anyone else. Mieville himself is a Marxist, but if that isn’t a picture of capitalism, I don’t know what is. The empire thinks the liability of owning the capital is too much, but they would love to lease, and the natives are free to share in the value.

Now of course not all of the downsides of colonialism arise from the colonizers being evil fuckers. Addictive substances introduced with varying levels of intention have resulted in events that might fairly be described as “genocide” on multiple continents, and I don’t think Embassytown glosses this. But what I think may ruffle feathers is that in this story, a colonist “saves” the natives by “elevating” their conception of the world.

Yeah, I don’t love that either. Still, I think there’s a perforated line where you can tear the book’s themes to save it. Set aside the particulars of Language for a moment–they’ll be relevant on the other side of the tear, but on this side let’s simply examine the colonial commentary alone. A generalization from this narrative that is obviously true is that cultural exchange has a significant potential for harm. In history, this is most visible in the transmission of European vices and poor hygiene, but it is a much stronger claim to say it stops there than that it doesn’t. I think the sci-fi style question that Embassytown very reasonably asks is whether it is possible to acknowledge certain directional harms of that cultural exchange and provide mutually agreed-upon aid to mitigate those harms. A key feature of this story is that even though factions align in opposition to each other, they are still all in agreement that this addiction thing is apocalyptically bad, and the only solution that will resolve it is one the Ariekei themselves choose. I think that this, as a prescriptive cap to the interpretation, is not in itself an offensive assertion.

Now on the other side of things, consider the Language. For a number of reasons, despite the unfortunate conjunction of the Ariekei’s shift in linguistic culture with the aforementioned colonial story, I think the particulars of Language and its evolution place it in a separate allegory. Calling it a philosophical allegory would be eliding the point: It is an allegory of philosophy itself. Think about it. Capital L Language is a very strange concept, even by sci-fi standards, and if this were a run-of-the-mill white savior story, that strangeness would be wholly unnecessary. If you want to make the natives wrong, there are easier ways to do it, but Mieville didn’t make the natives wrong–it’s the exact opposite! Language is both thought and Truth. It obviates epistemology. Human language is referential because our experience is unreliable. We need reference points to reassure ourselves and others that we know anything at all, but the Ariekei don’t have that misunderstanding. Their map is literally their territory. They still have a Westword-style “those words don’t sound like anything to me” when an Ambassador says something that fails to compute, but for the most part, this is a species entirely unconstrained by one of the most fundamental handicaps of the human experience. It’s no wonder, then, that Avice’s xenolinguist husband, Scile, reacts with almost militant horror when he discovers the emergent cultural phenomenon of Ariekei attempting to lie. Here is an experiential wonder of the universe, unlike anything ever discovered before, and human influence is already destroying it.

So think like an economist in this case. Do the cost-benefit analysis. List out the pros and cons, quantify them if possible; it’s easy to not question why we do what we do when there isn’t any alternative, but here one is. And while an anthropologist may very reasonably retreat from this exercise for fear of the bias-wolves lurking in the hills, we shouldn’t be deterred. In real life, that bias might literally kill people, which is why we sometimes write books to explore these sorts of problems instead of field-testing our solutions.

Since Scile’s stance is the first to disrupt the flow, we’ll look at that first. Why might the disruption of Language be bad? Obviously, change is not always good. Ariekei culture–which, it’s worth reiterating, is not especially well-understood–is deeply rooted in Language, so any linguistic revolution will almost necessarily mean cultural upheaval. Even if the Ariekei are “better” on the other side (hard to evaluate and extremely far from certain), some of them are going to get hurt along the way. Assuming you care about them, your prior should be toward caution. Moreover, even though the total benefits of the Ariekei’s linguistic status quo may not be legible, we can see some aspects that are clearly prosocial. Social trust and coordination are crazy valuable and hard to establish, and being unable to lie automatically overcomes the hardest hurdles for both, to say nothing of the reduced social friction from the much higher fidelity by which the Ariekei are able to articulate concepts. Tertiarily (from the philosophy of this argument–though Scile, et al may value it more highly), there is the aesthetic value of this truly unique linguistic (and, to a certain extent, metaphysical) phenomenon existing in a place where you can reach out and touch it. The alternative has potential to destroy it, and that is not a negligible cost. Even if you accept that the giant panda is dubiously fit for survival, you’d still kind of rather it wasn’t extinct.

On the other side, pinning your language to your thoughts, to what is literally, verifiably there, is limiting in ways you might not expect. Consider that the Ariekei are a technologically advanced civilization (they have made technological advancements that an interstellar empire has not), but they’ve never been to space. They have no interest in space–how could they? It being unknown to them means it is not, and it being not, means it can neither be spoken nor thought of. Needless to say, this has downsides in much more mundane ways too, hence the Ariekei’s reliance on living similes.

But this is all fairly surface. It’s what the book lays out for you, alongside the embassy’s political motivations, leading up to the assassination of Surl/Tesh-echer. The question one ought to be asking oneself: The megacrisis, the EzRa-induced addiction–is that explainable by the philosophical nature of Language (without a need for some additional MacGuffin)?

I think it is, mostly, sort of. It requires us to fill in a number of gaps as to what it means to speak Language badly. Mieville provides a hint, though: In the creation of EzCal following the death of Ra, the protagonists operate on the assumption that a key ingredient in the “god-drug” is that the second voice in the second voice in the speaking pair hates the first. For normal language, this would be irrelevant, entirely outside the model, but for Language, where both voices are meant to come from a single mind, it makes each word a negation of itself, infusing it with a whole bunch of meaning not implied by the actual phonemes. The scale of the crisis is MacGuffin, of course. The reason EzRa’s voice is so much more narcotic than previous observations of the phenomenon is that Ez is, himself, an engineered hyper-empath for whom being hated by his cybernetically-linked second voice is a uniquely-affecting experience, which comes through in his Language. But consider what this implies about the Ariekei experience.

It is obvious that scientific discovery depends in some measure on epistemology, but those roots spread wide underground. To paraphrase Lou Keep, Kant claimed that his work was meant to save the sciences, but what was really at stake was everything else. Interpretation of experience relies on validity of experience, which means that epistemology has fairly serious implications for aesthetics as well. The Ariekei don’t really have epistemology, but they have plenty of science. Provided your biology allows it, you can just go places to expand your mind. Skipping over a lot of details of this argument (this isn’t really the venue for philosophical groundwork), the Ariekei’s empiricism is awesome, but their predictive math is not. And if all of your experience is high-fidelity empiricism, all of your aesthetic values are going to center around anomalies.

The retreat, then, from Language’s perfect alignment with reality, to semiotics, to reference, is really about values. It’s about freedom to define what is good, independent from the balance of Science (the good is minimizing anomalies) and Suffering (the good is minimizing pain) which the Ariekei were strung between before. It’s the ability to access philosophy, tools to make the incommensurate commensurate.

Of course, Mieville doesn’t overextend thai to a stance on such thinking being better. Some Ariekei are unable to unlearn Language, some choose not to, and the society of cured is able to engineer workarounds to keep the addicted alive. Nor is it a perfect exploration of the topic (to say nothing of my own no doubt stunted understanding of it), but even so, there’s a lot there. A lot of things to think about, biases to unlearn, new looks to be had at this series of images we call life, and, of course, new words to describe it all.