It’s been a little while since we’ve been here. If you need, check out the previous posts in this series first. Also, because you can never sit down and read just one thing, I linked an article in my first essay on this topic. If you haven’t read it yet, you should now. It was always relevant, but it connects the philosophical parts of this to our reality better than I ever could.

A little under two months ago, I started this blog, and the first substantive thing I posted was about choices in video games. This will be about choices as well, in video games, in life, and, more deeply, in what we value. It will be a turning point–the previous essays have been getting at the metaphors underlying Dark Souls’ setup. Now, we get to ask the question: “Why?”

I.

I’ve talked a lot about “Truth” in the last two essays without really getting into what it means. This is meant to be respectful. The only sense in which I am the first to say any of the things I’m saying is the sense in which they relate to Dark Souls (which is still a little surprising, but I’ve beaten that horse enough already). Still, since this runs the risk of sounding completely insane without clarity on that concept, I want to be explicit: Truth is something that humans value–we all intrinsically want the things we believe to be true. This starts, obviously, with perceptions of reality, but then it goes and starts a bar fight with religion and science. For those interested in the hard sciences without a background in philosophy, it may be difficult to believe, but the advances in scientific thought that propelled us from the Middle Ages to modernity were based heavily on metaphysics. This starts with the question “If I can’t trust what I see, how can I know anything?” but the high-level ends up being this: We created/reinforced gods in service of Truth. We then ask whether we need gods and, unable to see their purpose, begin devaluing them. Then comes the best part: Some asshole asks whether we need Truth.

“Is this still about Dark Souls?” Sure, just replace “Truth” and “gods” with “Flame” and “Lords”, and we’re hunky dory. More pointedly, in Dark Souls, that asshole has a name: Kaathe.

Darkstalker Kaathe is a primordial serpent. He goes way back to when the world was mist and trees and dragons, and this means A) he has a complicated relationship with the Truth and gods metaphor that I don’t really want to get into here and B) his age grants him a view on the situation that doesn’t have a good real-world analog. Anyway, he starts a cult, they kill a lot of people, and the powers that be flood a city on top of them. This is the advent of nihilism in Dark Souls. The details actually are pretty interesting, but the Abyss is going to get its own essay. Kaathe is coming up here because he’s the one that offers you an alternative in your quest to save the world. Oh yes, you were on a quest–didn’t I mention that?

II.

That isn’t a gotcha at all if you actually played Dark Souls, but I know for a fact that some of you have not. Recall from the intro:

Thus began the Age of Fire. But soon the flames will fade and only Dark will remain. Even now there are only embers, and man sees not light, but only endless nights. And amongst the living are seen, carriers of the accursed Darksign.

The plot of the game–which we’ve avoided discussing up to now–is you exploring Lordran in fulfillment of some vague prophecy that no one seems to have respect for, but then you complete the first piece, ring some bells, and a giant snake blasts out of the ground where you first showed up. His name is Frampt, and he tells you that your purpose is to succeed Lord Gwyn and link the Fire, prolonging this golden age. He’s not terribly specific about what “linking the Fire” means, but man, becoming the successor to God? That seems pretty neat, and so this becomes your quest: You must gather the souls of the gods and use them to open the way to the Kiln of the First Flame, that you may link the Fire.

That goes about as swimmingly as things can go in Lordran until you find Kaathe at the bottom of the Abyss. He has a counterproposal for you: Why don’t you just…not do that? Gwyn went and linked the Fire, sure, but he was a pussy, scared of the dark or something. It’s not like an Age of Dark would actually end the world or anything. This is when he lets you in on the piece of the creation myth that doesn’t get repeated:

If you remember the other gods from the second essay, you remember that they each represented something. Gwyn was light, the Witch was chaos, Nito was death, but there was another, “so easily forgotten”. The pygmy found a special soul within the Fire, the only one named without a possessive: the Dark Soul. Gwyn is not happy about this for reasons that aren’t really clear without the metaphor, and he goes to great lengths to ensure that the descendants of the pygmy don’t flourish and the dark does not overpower the light. On the first count, he clearly failed–you’re here after all, but you can’t say he wasn’t motivated. To stop the guttering of the Fire and the coming Age of Dark, he used his own body as fuel..

There are a number of metaphors here, let’s unpack them:

First, note the obvious parallel to Christianity, but also note the dramatically developed context. In this version, God still sacrifices himself, but there’s an added element: fear. That he fears the dark here means he fears its impact on the metaphysical–it is not simply love for another substrate of reality. So what danger does the Dark Soul pose?

The Fire is Truth, light emanates from fire, and that makes Gwyn a manifestation of true things. The Dark Soul, then, is what’s left. Not-true things. Lies. “Seems bad.” Oh, really? I’m sure it does, but can you make a case for it without appealing to Truth as a value? Lies are easy to detach from the types of harm we hold to be bad based on other values, but still, they feel wrong, it stings your character to lie to others, and for some reason, you can’t lie to yourself. Truth is king, we’ve put everything else in service to it, and, of course, why would the Fire embrace its own death?

And so, Kaathe offers us a choice: Immolate yourself, the successor to the gods, in service of Truth, or walk away, embrace the lies, and usher in an Age of Dark.

III.

About the most famous thing Nietzsche ever said was “God is dead”. Sounds about right. Death and Chaos are toast, you murdered them on your way here. Light is in the process of burning, soon to be spent. All of that may seem good or bad to you, but to Nietzsche, it was an inevitable result of that initial enshrinement of Truth as our highest value. It brought us through the Stone Ages, to antiquity, to modernity, to the point where we are capable of contending with the forces of Gaia on a nearly even playing field. Truth has brought us power even if we’ve had to sacrifice human meaning to get there, but that was a long-term decision. Now, finally, we have the opportunity to course-correct. Truth is going out, and the sun has reached its median in the course of human history. Nietzsche called it the Great Noon, but as you might guess, the Dark Souls take is a little different.

Interpreting Nietzsche’s options from Lou Keep’s essay, you can translate them to the Dark Souls metaphor like so: The last man is letting every value burn to nothing, ceasing our advance to power, and living on in the twilight until at last we die. Affirmation is embracing the Dark, learning how to lie, and adopting a new hierarchy of values in Truth’s place. Of course, affirmation could mean that we are affirming an ideal that does not exist (which isn’t ideal), or it could mean affirmation of the here and now. The problem is that it’s very hard to do either if we can’t lie to ourselves.

However, Dark Souls allows for two other options, one of which isn’t well explored by Nietzsche’s framework (which we’ll save for last), and one that…well, that he was reacting to in the first place. That one, we’ll discuss next.

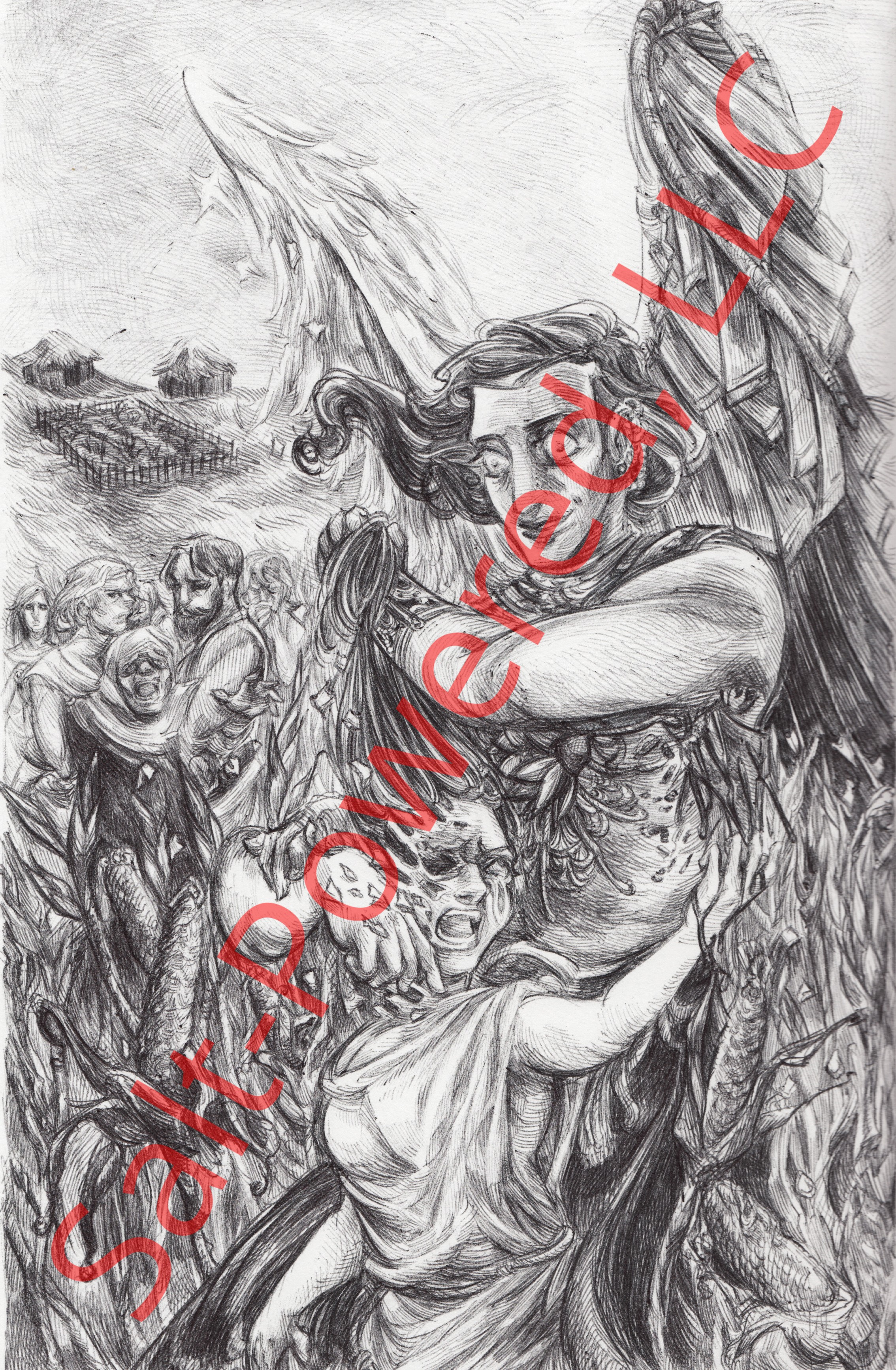

Top Image: Screenshot from the launch trailer for Dark Souls 3, I do not own it