Purchase a Little Piece of Suffering Today!

Coming from here…

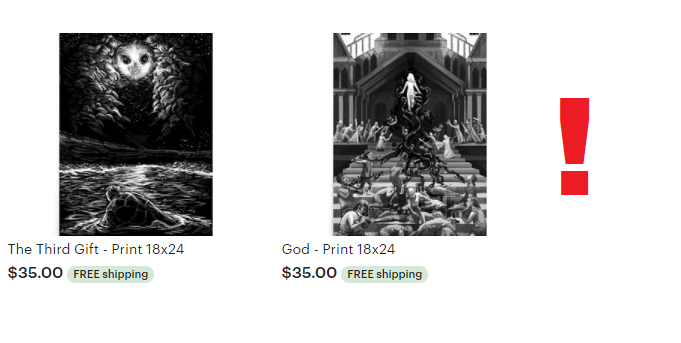

This is so much later than “this week”, but testing shipping took a hot minute. While work is ongoing on literally everything, we’ve set up a shop! Offerings are limited right now, though we’re working to set up more soon. But still, if you’d like to buy a print and support our work, we’d be very grateful.

Shells of Dead Things

This past weekend, I visited my parents, and in keeping with ritual, timeworn in the considerable period since I left home, I picked up another box of childhood possessions needing allocation between the designations of “keepsake” and “trash”. In it this time, I found a boardgame, a pre-production copy given to me by its designer (my high-school girlfriend’s father) at around the time of its retail release. It was a spiny memory, hence my writing about it now.

If the game were a seashell, it would be an unremarkable one, chipped, dull mottled white and brown. It was a physically clever design, but when all was said and done, it was just a limited set of sudoku puzzles, rendered in three-dimensional, physical space for reasons that I’m not entirely sure were thought out. Predictably, it had little appeal to the sudoku demographic, and as far as I can tell, there is no longer any way to acquire it. Like a seashell, it’s just detritus now, washed up on a beach, ejected entirely from its medium of existence.

Also like a seashell, it remains as a reminder of something no longer here. Game project failures are a dime a dozen–even the best developers have tons of them–but this man never got another shot. If memory serves, within a year of giving me this gift, his cancer returned from a ten-year remission and took him from his family and whatever projects he might have intended as a second swing. There’s a true but tired moral here of how life (and its grim consequence) will relentlessly fuck with our best laid plans, but what I felt as I picked up that game was just a strange, calm shiver, a slimy, ephemeral thing crawling up from the sea to remind me that the shell I hold is important, that it once meant something.

The meaning there is not the same as the moral, and of course it’s difficult to parse. But even though I can look down at the sand and see the horizon of shells, stark, white, legion at the water’s edge, I know the apparition isn’t wrong. This one did once mean something, and my own unique ability to remember it suggests it’s worth keeping.

Infrastructure

Sorry for the relative radio silence. Work has been ongoing, albeit slowly. I have a relatively exciting update coming this week, but I wanted to drop a small preview today (while I’m thoroughly engaged):

Image: The Third Gift, by Rae Johnson

Humanity’s Eyes, Part 4

Continued from here. This will be the final part–I will post a unified version (like I did for the LaSein Account) soon.

I lived in the wet

For a long time

This odd striving place

Where things kept growing

I learned the humans were burning down the last bits of the forest

Hacking off the trunks and limbs of the trees

Killing the furry people who hid behind them

They were very harsh these humans

It was no matter to me

I did not depend upon the trees

I buried myself in the sand and the dirt

The drying of the forest felt good on my thick and chitinous skin

I could smell the humans, the fuzzy creatures, or my marked

From far away. I remained out of sight

Anytime I wanted I could kill a human or two

When they were particularly lingering or loud

The humans cut down the entire the forest some years in

All of the creatures that lived in the trees were dead

My marked humans began to leave

Walking up the mountain, where their scent eventually disappeared

They left me

In this moist and dirty place

And I started to reflect

Upon my life

The old man

And the little girl with the emerald eye

Maybe I had wanted too much from her

From all of them

Though, I don’t know if I had ever wanted anything

Survival maybe

Gifts maybe

To be seen, to be near

I saw in myself for the first time a sort of softness

Beneath my now granite-like hide

I understood I really did like loving them

My former little group of marked humans

The girl

And love was what it was.

I started to take care of little creatures I found

Letting them live in my hide

Providing them little goodies, food bits, bugs I found

I enjoyed these little creatures scurrying all over my body

Then the mountain came crumpling inward

Like a strange earthquake

A horrifying sight

Dust billowing everywhere

Moaning and twisting of rock

The tops of the peaks came below the clouds

And beneath the clouds they shined like gold

I smelled smells I had never smelled before, along with metal and fresh growing plants.

There was much blood then

Those next days

I smelled much blood

And the tang, the sour taste of magic being cast

Me and my little creatures waited

Burrowing in the sands

Eating, avoiding

Living as we did.

Then I smelled my marked

The ones that had left me so long ago

Sand Lips. But not Sand Lips. A child maybe that had grown

And the unknown scent of something. Several things, living, but mysterious.

The humans now crowded the top of the mountain

And my marked were walking down

down into the desert

Deep into the heat, the land of no water,

the land of the dry, the beautifully dry

I walked towards them

These marked and the mysterious others

Me and my creatures were going back to the land of the hot

My true home

And I gave these new creatures little gifts

Just as the girl had done for me

I watched over them.

Not a part of them, but near them

A demon

A crag

A landmass

Sharing its home

Humanity’s Eyes, Part 3

Continued from here.

As the sun grew hotter the days grew longer

The earth became drier

Fewer and fewer plants grew up in the damned wastes that were my home

My odd little collection

Of marked up little humans

Was suffering

Their people, the older ones, but not too old

Would go further and further into the wastes

Hoping to find and bring back a large cactus

Or find a small pool of water

Or a beast whose blood they could drink

Some of them got hurt when one of those beasts found them instead

The next days I noticed they were packing

Gathering together their little makeshift homes of canvas and bone

Loading them on sleds

They were leaving me

This land of sand and sun

Leaving this waterless pit

As they left, they left behind a final bowl for me

A final farewell of types I supposed

My shovel-like fingers took up the offering and it crunched in my teeth

I felt alone

For the first time in a long time

I wished for their odd presence near me

I missed the giggling screams of their children

Missed the strange noises they made at night

Missed their footprints in the sand

So I followed them

Their stench was lingering long in the desert

Clear tracks.

I didn’t wish them to notice me following them

I don’t know why I cared

But I wished to remain a secret

My long legs and massive arms easily moved through the desert

I followed them many nights

Just past the point of sight, a day away, no more no less.

The ground became thicker

Moister

Dirt

The bugs were different and disgustingly plentiful

Every little nook and cranny of earth seemed to have a bug inside

It seemed grotesque

My little pack of marked humans came

To a partially burned forest

With a mountain in the middle that stretched into a thick layer of clouds

And a massive human settlement

that stank like a decaying corpse

Full of humans

Normal humans

The kind covered in crunchy metal and hateful looks

I stayed away from this human settlement

And found the first pool of water I had ever seen since I was a child

A small puddle and I saw my face

Spikes were ripping out of my carapace in hellish angles

My deep seated eyes were even darker yellow than I recalled

My snout was sharply pointed and looked almost like a beak

I was so caught by the look on my face

The look of my face

The look of me

I did not notice the human until they screamed

I turned towards them

They were a quarter my height

An eighth my width

Built like a tree where I was a mountain

They threw a spear at me

Like I was a dog to be killed

They pulled out a small sword and screamed in rage

Their spear hit my outer carapace

Jammed inside

Stuck like a twig

They ran at me with their sword

I lifted my thick shovel like hands

Their sword bit into my wide and hardened fingers

Their sword got stuck in me

They looked down in shock

Up in fear

My hands crumpled around them

Squishing this human’s meat

Pressing their limbs into their body

Picking them up

I held them in the air, immobile, helpless

Thinking of squishing the blood from their meat

But I instead I held them in front of my flat yellow eyes

They asked me what I was

I said I was the crag

They spoke strange

Bouncy and fluid

But a sound I oddly did not fully hate anymore

They asked me if I would kill them

I looked at their pulpy limbs

Soft squishy face, tears at the brim of their eyes

I said no

If

I looked at the human

Told him the name Sand Lips

Confusion covered their face

But also recognition

I told them to ensure Sand Lips was safe

Along with the little ones Sand Lips kept

I told them to ensure these marked were safe

Or I would smell their scent

And I would kill them as prey in the night.

I breathed deep into this human, learned his smell

I stared into their eyes and asked if they accepted the terms of my agreement

He said yes. The fear in his eyes was fresh, moist, and sweet.

I dropped him

He ran.

I smiled.

I had no more hate for humans.

They were small and afraid.

As they should be.

Part 4 here.

Humanity’s Eyes, Part 2

Continued from here. As before, by Leland.

The next many years were long and harsh

They were also lonely, but I had no idea what that meant at the time

In the beginning I was like a piece of sand.

I blew from place to place

I felt nothing on my insides.

I ate

I drank

I killed

I moved

Life was a never ending cycle of survival

Though my body continued to morph and change

My chitinous ledges grew larger

My fingers grew thicker and harder

I could tear out huge piles of dusty earth

And suck out the soft crunchy creatures that burrowed beneath

I was a moving land mass.

Not a monster

A thing

An object

My hate roiled inside of me

But without eyes watching me

Reinforcing that hate

It began to bake into my bones

But the eyes

The eyes of my mother

Of the only girl to give me a gift

And the smell of that lock of her hair

Was still fresh every time I remembered

I would cringe in those times.

As the years wore on that pain stayed true.

I avoided the smell of humanity

That would drift in with the dusty blasts of air sometimes

I preferred my thick and rigid solitude

As I roamed one day I smelled blood

Fresh blood

Active blood

Human blood.

I sat on my haunches. Staring into the far setting sun.

I decided to pay back the one act of kindness I had received

And walked towards the blood.

The sun had almost set by the time I descended upon the moving human

One of the grit, the marked, the human rejects I had been raised with, was sliding in the sand.

Legs inert and twitching behind them

Blood staining the sand as they moved.

They had a fierce and hard look in their eyes, dust embedded in their teeth.

They first felt my shadow land upon them

They looked at me

A moving mountain

With my fetid yellow eyes

They showed fear on their face. Or maybe acceptance. Maybe denial

Something firm and unrelenting.

I spoke the language of the desert to them.

The words sounded odd and strange in my mouth

They were shocked I could speak

And relieved.

They said their name was Sand Lips

And they needed to send a message

That the Mukori were coming

To kill the Kamai

Their exhaustion took them

And they fell into the sand.

I looked at the grit. The marked and scarred human. Helpless. Desperate. Clinging to life over some words they claimed needed to be heard

Heard by someone human.

I stared at this breathing corpse for a while

Thinking of this message

The Mukori, the Kamai, Sand Lips

Names felt strange in the desert

I was a demon, a mountain, a pair of yellow eyes

Sand Lips.

Sand Lips.

I hated names.

I hated these monikers of humanity

I hated them in my ears

In my throat

Along my tongue

I pounded the desert

Threw a massive boulder,

Flung a mountain of sand

Trying to throw it out of me

But it was stuck.

These names

These filthy human names.

The desert could not take them from me.

For the desert was no home for humans.

Only those filthy human camps could take these names

I screamed

A sound so loud the sky quaked

And the moon cried

I lifted the filthy human over my back

Limp and helpless

A sack of barely breathing meat and pus

I moved my body weight forward

Let my legs press against the earth under me

I loped

Towards the humans

The sickening smell of the humans

I saw their little fires in the distance

The ground under me flew

The cool wind whipped into my eyes

The earth stretched and narrowed and the fires grew larger

I came to the fires, the humans all around, all marked, all cut, all children of the grit.

I crashed into their makeshift home

This little gathering of scarred humans

Humans that were so small

Looking up in terror

Shear terror

I was still a demon

And they had no idea what I was here to collect

I put down the limp sack of meat from my shoulder

And I spoke those pus-riddled human words

The Mukori, the Kamai, Sand Lips

Told them they would die.

An old human came out

Thanked me

Whatever that meant

Said they knew not who I was

Said they had not seen one of my kind for a long time

My kind

My… kind

Tears began to leak from me

The elder lifted a bowl up to me

Some sticky nectar of the cactus fruit

I ate the bowl.

This was the second human to ever give me a gift

I left

Went back to the dark

To the desert

The sand and the rocks

The moon and the sun

The bugs and the earth

But I continued to smell these humans

And I did not go far.

More humans came

Clanking humans

Loud humans

Humans laden with the pungent, sour smell of relics

I killed these humans, before they could see me, before their eyes could look at me in disgust

Like a pack of bugs they crunched in my teeth

I Split them in half

Popped them like flies

I left them dead there.

They were too loud.

Entitled, angry, and hellishly human.

Their trinkets smelled sweet

And I ate them

They powdered in my teeth

Leaving my mouth sour and salivating for days

I decided this part of the desert was mine

And these cut and marked humans

The ones with the sand lips

Could stay in my piece of the desert

And stay they did

Leaving little bowls of cactus nectar out for me

I felt a touch soft towards them

Like a favored rock or time of the day

I would not choose their death

And they grew older and smaller

And I grew larger and larger

Part 3 here.

Humanity’s Eyes

A poem by Leland for Rale.

When I was born I was betrayed

My mother tried to kill me

For I was born wrong

Sickness marked me all over

I was a cur a curse a wanton filth

She thought a kindness was death

She threw me to the desert

But the desert men found me

Took me and raised me

As a second hand slave I was raised

A child of rejection and poverty and begging for scraps

I ran between the stalls of the desert men, not unhuman enough to kill, not human enough to love

We roamed through the desert

I stayed mostly with the children of the grit

Marred and scarred and blackened and raw they would not hit me

As I got older, the sickness that flaked my skin grew harder and tougher

Stranger by far, long thorns grew from me, and my eyes became a fetid yellow

I began to be called the demon. The demon they whispered, no longer in contempt, but also in fear.

As my muscles grew thick and crusted like a humanoid crab, my eyes began to wander

I hated the world as the world had hated me

But there was one little girl who treated me with kindness

The daughter of the leader of the desert men

The daughter of their sultan

She was a kind girl with a horrible scar on her face from an injury from when she was a baby

She had one eye that was emerald green

She placed bowls of water out at night

I knew they were meant for me

Her emerald eye reminded me of the eyes of my mother

I felt that my mother had killed herself and she had been reborn,

Now she was here to take care of me like she never had before

I got older and older and I never stopped growing

The other boys stopped growing, but five years later, they stood at my shoulder

Then they stood at my chest

Then they stood at half my height

The fear in the desert men’s eyes grew

Their deep religious belief in the martyr was being pushed

They began to talk about the “Demon among them”

I watched the little girl grow up.

She was beautiful

And kind.

Long brown hair and that emerald eye

My mother’s eye

She started to leave food behind with the water, and flowers, and then a lock of her hair.

I kissed it and nuzzled it and tried to breathe it inside of me

And I would watch her from the corners of my eyes.

As I roamed through the tent filled trading stalls, resting on my knuckles, clawing into the dirt with my back feet.

She came one night

And touched my face

Not afraid. Not like the others.

She held my face that night

And she cried

Her one eye pouring sweet and salty tears onto my mountainous, grotesque frame.

The people came the next night.

Her father came the next night

The torches came the next night

They told me to leave.

They pointed towards the desert

The said go anywhere but here.

My humanity had run up in their eyes

They owed me nothing

The savior owed me nothing.

I crawled into the desert

The aching moon at my back

The harsh sun on my face.

I walked through the desert, lumbering like a barge as the heat cracked my skin like stone

I licked rocks for water

I smelled foul nests of bugs using my strange and sensitive nose

I ate the creatures

While I thought of her

My mother reborn who abandoned me again.

As I walked into the heat of the sands

And the ice cold nights

I realized I was never human.

And I no longer wanted to be.

Part 2 here.

Top image: “Hazeen’s Man of the Clouds”, by Rae Johnson

The Nicholas

April 2, 1920

It was a clear morning off the New England coast–approaching the southerly latitudes of Maine, if memory serves–and though the waves were calm, April’s lingering chill had yet to pass on, crawling, it seemed, up the sides of my boat, around my ankles and settling uncomfortably, like some odious shawl, about my shoulders. I had sailed north only recently, having spent the winter fishing down in the Gulf, and the swift return to my summer grounds–premature, for a bout of restlessness I now vehemently cursed–had left me as yet poorly acclimated to the northern spring and robbed of any enthusiasm for the productive use of my location. In my shivering solitude that morning I had cast two lines, and though I’d gotten bites on neither, I was having difficulty mustering the will to bait a third. I recall it was in that fraught quiescence that I took notice of the irregularity surfacing some forty yards off the port bow.

To my first glance it seemed like jetsam or some other detritus, having the texture of maritime vehicularity without a form I could identify as any particular boat, but as more of the mass emerged above the waves, my befuddlement became something more akin to awe. My previous confusion in identifying the object, it seemed, had lay in my assumption that its form would be singular when, in fact, it was comprised of numerous vessels and the pieces thereof. Before me were hulls of dinghies, canoes, fishing boats, shattered boards and beams lashed haphazardly against great sheets of black rubber in a jumbled ellipsoid that, from far off, might have been mistaken for the carcass of some colossal leviathan. For all the strangeness, though, of this great, nautical garbage heap, I still found myself ill-prepared for the sign that then surfaced on its carapace–glowing red neon, proclaiming it to be The Nicholas–or the concrete suburban front porch, flanked by flaccid strands of potted seaweed, which emerged beneath it. Even as the door of the porch slammed open, and a ragged man stepped out and hurled a bucket of something foul into the ocean between us, I could only stare, speechless. Ultimately, it was he who called out to me:

“Aye, laddie! Watsonismouth?!”

I shook myself awake. Being then unable to place either the man’s accent or the meaning of his query, I called out as much and motored over on the supposition that proximity might serve to make better order of the situation.

He clarified as I drew closer: “Sonny, let meh ask ya ferst: What’s in ya mouth?” I might have guessed his previous call had been delivered in some dialect of the British Isles, but now his accent had drifted westward, seeming suddenly more appropriate for a denizen of the Carribean (and, I will admit, suggesting an origin I would never have guessed from his appearance). Beyond the vagaries of his delivery, though, I was also rather bewildered as to the substance of his inquiry. My mouth was quite empty, for though I normally partook of a smoke at this hour, I had dropped my pipe somewhere on the deck, amidst the shock of his vessel’s emergence, and had since lost track of it. I indicated as much to him in my reply.

“No, son,” he clarified in an abrupt Mississippi drawl. “It’s a mattah of circumnavigation. We’s tryin’ to get at what’s in ‘eez maouth, an if yer knowin’ what’s in yer maouth, then that’s a tack on the chart, ‘cause what’s in yer maouth properly ain’t in ‘eez maouth, ya see?”

I did not. I inquired–skeptically, for I was growing increasingly certain that this man was in something of an unpredictable state–as to whose mouth we were investigating.

“Not whosemaouth, son. ‘Eezmaouth. Like beezmaouth, if’n ya know the rock, ‘cept withaout that certification of a job done at the utmost pinnacle o’mediocrity.”

The conversation had, at this point, attained the clarity of a bayou, and my only remaining answer was a blank stare. He shook his head sadly.

“It iss clear to me”–his accent was now that of the Mexican fishermen I’d dealt with so frequently in the Gulf–”dett we fall on fundamentally different sides. No matter. Diss iss not a sorpraiss. Do you haf any feesh?”

Alas, I did not have much in the way of a catch. I’d trawled no nets since arriving up north, and I’d no plans to do so for a few days yet. I had a pair of mackerel I’d caught the previous day, but that was it, I told him.

“Oh, don’tcha know dere’s nuttin’ to be ashamed of, young feller. I’m just lookin’ for a bite ta’eat is all.”

It sounded like Upper Midwest to me. Minnesotan, perhaps? It also occurred to me that despite the man’s graying, unkempt beard and repeated references to me as a young man, he did appear, in all other respects, to be at least twenty years my junior. Befuddled, still, but acclimating to the ersatz temperature of the conversation, I offered him one of my mackerel, which he eagerly accepted, biting–rather aggressively–into the fish’s flesh right there on his vessel’s concrete gangway. Then, shouting something about “makin’ you rich” through a full mouth and what sounded like an American’s (decidedly poor) impression of an Australian accent, he dashed back through his door, leaving me to the continued ponderance of the monument to madness which was The Nicholas.

In his absence, I began to notice a number of unsettling details lodged in the crevices of its unsound construction: Marionettes, features scrubbed clean by brine, dangled among the mishmash of hulls and rubber, alongside inscriptions and engravings in those surfaces in alphabets I did not recognize even from Dr. Sterling’s texts on the Oriental scripts. Place to place, I could see protrusions from the rubber that looked like the spiraled horns of narwhals, and just past the threshold of the vessel’s “front door,” I saw hanging vines and foliage as if within were some dark jungle separated by unnatural, great distances from the semi-boreal sea where we drifted that morning in truth. These items were, of course, in no way sinister, and I had no means of rationally justifying the fear for my soul which I felt there, in silent anticipation of the man’s return, except, perhaps, for the vessel’s unignorable suggestion to me that rationality had ceased, in this circumstance, to be a meaningful boundary. However, my fear passed unactualized, and the man soon returned, heaving over to me a bulky canvas sack.

“My recommendation,” he said to me, all pretense of brogue or twang gone from his voice, “is that you bring that to an office of the United States Navy. They will pay you for it. Or pay you to keep quiet. Or both. Please pass on that it arrives to them courtesy of Captain Kneecap.”

With that, he disappeared back across his threshold, and, his door scarcely closed, The Nicholas dropped rapidly beneath the waves, the shock of which rocked my own boat violently. Once I steadied myself, both physically as well as from the emotional disturbance of “Captain Kneecap’s” presence, I examined the contents of his gift to me.

Inside was something I found appalling, though not to the exception of an urge to examine its nature. It was a body, headless, human-shaped, though clearly not human, for it was comprised not of flesh but of some metallic substance resembling steel but impossibly light for its bulk. Between its noticeably elongated fingers and toes was webbing of a material I could not identify, and though they had been torn from it, I saw sheared joints on its arms, legs, and spine where fins might have once attached.

I did not know what to make of the corpse-mannequin, but if the Captain’s words were to be taken with even the slightest skepticism, there was nothing there for me to glean. I was to be an intermediary in a conversation to which I desired precisely no connection. Though I hesitated at the thought of the Captain’s promised riches passed over, I threw that “gift” back into the ocean that day. The Nicholas was perhaps not the strangest thing I have ever seen upon the water, but I hope all the same that I never see her or the Captain Kneecap again.

The Creator Is Dead

Since the beginning, for time countable and yet unimaginable, we knew that this would come to pass. Why is dead. The Creator is dead, and I…do not know what I should feel from this. We have no need of sorrow, nor relief, for His presence was not a burden, and what we did not know, we knew He kept from us. The trepidation that I now second guess is for that change: It is now time for the Architects to find the truth that Why kept from us for our aeons of safeguarding His Edifice. We cannot resist it–the need to know is in our nature, but where we lacked the ability before, our shackles have been broken.

The humans around us remain oblivious to this change, oblivious to their imminent reckoning, for now, at last, we may delve and extract the Creator’s intent for them. Among the Architects, expectations are conflicted. El is confident we will find a justification for the Edifice’s uninterrupted continuation. I am not. Why’s death was not an accident, it was not unexpected; He could not have intended it as anything other than a transition–of this I am sure. El may speak our unanimity, but until it may be spoken with one voice, I must question his judgment.

For now, I look to the stars, our heretofore forbidden frontier. Perhaps in the alignment of the bodies beyond this vessel’s atmosphere, I will find the purpose that our Creator has forever denied us.

-See