A review of Alice, by Gary Gautier. Obligatorily, the “low-class art” in the intro refers to my own genre work and not the book being reviewed.

It’s a strange paradox of the modern world’s educational edifices that aspiring artists only receive meaningful training in the production of low-class art in the context of great prestige, at the greatest expense. I mean, sure, you can take a few free credit hours of “modern film” your senior year of high school to help pay off the district’s gambit to persuade you not to spend your lunch break on the bike path across the street, getting blasted on some guy’s blend of low-quality cannabis, but that generally doesn’t train you on much. Meanwhile, if you would like to attend USC’s high-cachet rockstar school for approximately $1 bazillion per year, you are suddenly in a very competitive environment.

The economics are deceptively obvious: Cynically, teaching enduring classics shields criticism, absolves educators of the responsibility for excessive insight, etc. But the other side pushes hardest: Marvel is big business, and if you want to speak to the masses, the system will only spend the money teaching you how if it thinks you can succeed. Dollars are expected of you, so either put skin in the game or get to work.

All this to say, I did not attend rockstar school or its literary equivalent, so virtually all of my training in the written word has been on more highbrow material. I suspect this is common for genre authors like myself, where the glitz of speculative fiction was left as an exercise for the writer. Less common, perhaps (or not, I don’t know you), I really enjoyed that training, I have literary aspirations, of course I try to return to it often.

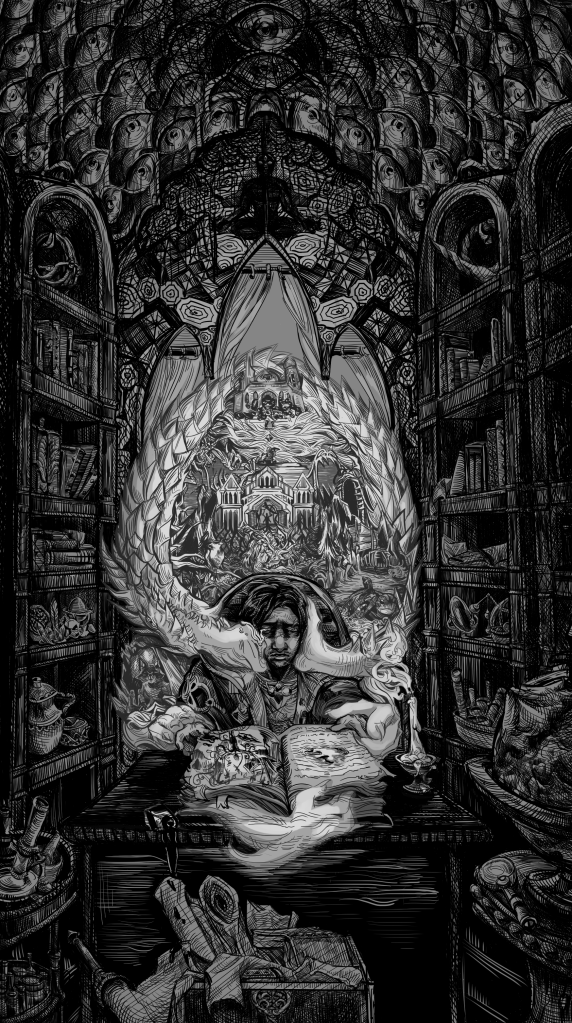

Today’s return is Alice, by Gary Gautier. Gary is a neighbor in the blogosphere (you can check him out here), and he was kind enough to consent to me posting this review. Unsurprisingly, I recommend the book–it’s a quick read, an enticing dream, a novel take on post-apocalypse. I make no claim to a “final” reading of it. I’m sure I missed a few things, but that’s part of the fun of analyzable literature: The point of the puzzle is that the solution is not trivial.

Before I get to the meat of it, I want to note that the below contains some spoilers. My isolated take is that preserving the surprise of Alice’s plot is somewhat beside the point, but if reading those sorts of revelations early bothers you, I encourage you to read the book and then come back.

Now: The premise of Alice is that Alice (the character) lives in an idyllic, egalitarian commune in the woods and is having some strange experiences. Like dreams but waking, less hallucination than astral dissociation, paired with the inexplicable experience of change. For example, in the very first paragraph, she perceives that the constellations in the sky have changed. Much is made of this, of course, and it remains ambiguous whether the change was material or perceptual. She mentions it to other characters, and they acknowledge something, but they seem mostly to be acknowledging Alice’s perception rather than a physical change in the world that is salient to them. These changes, alongside visions and conversations with individuals who are dubiously “there”, are bewildering and concerning to Alice, but it’s notable all the same how long she does nothing about it.

Okay, so the real draw here isn’t the plot. It’s the prose (which later validates the plot). It’s faespeak, highly simple, almost the literary equivalent of “plain English” legalese, but informal, hazy, and full of reference to commonly-understood memes. At the risk of comparing it to something it’s not really like, it reminds me a lot of Madeleine Is Sleeping, a very different book about dreamlike hazes. But it’s a book about dreamlike hazes. Whimsy is definitionally protean, and it takes the form of Kingdom Death: Monster just as well as that of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Her somnolence is technical, surface level, and her flights of fancy are more worldly than fantastical, but practically speaking, Alice is asleep. Part of this is literal–it is revealed that the ladybugs flying throughout the commune are robotic, designed to acoustically pacify the people around them–but much of it is still literary. Alice is chock full of circumlocution of the fact that, while she is very reasonably confused at the unfolding of her ethereal meta-world, she is neither incompetent nor dumb. She is clearly capable of synthesizing from the information she has, and she has more information than she should due to her metaphysical connections. But she still lacks agency for much of the book. Materially, this is the same reason most people lack agency: She doesn’t know what she wants. But this manifests as an aimless seeking of answers only to be shunted from her path, gently but repeatedly, by random happenstance, by people who also do not really know what they want but seek control because it’s there to seek. Psychoanalytically, this looks a whole lot like resistance, a projection of Alice’s inability to act, onto the external structures that theoretically should bind her but really don’t.

This perspective, that of the individual within the world, nominally surrounded by power structures meant to corral populations, but in reality gated only by their ability to control/change themself, to want things, to act, feels to me to be where Alice is at its strongest. This may be projection–I may still be high on Sadly, Porn, but the core thought is not especially uncommon. From Alice:

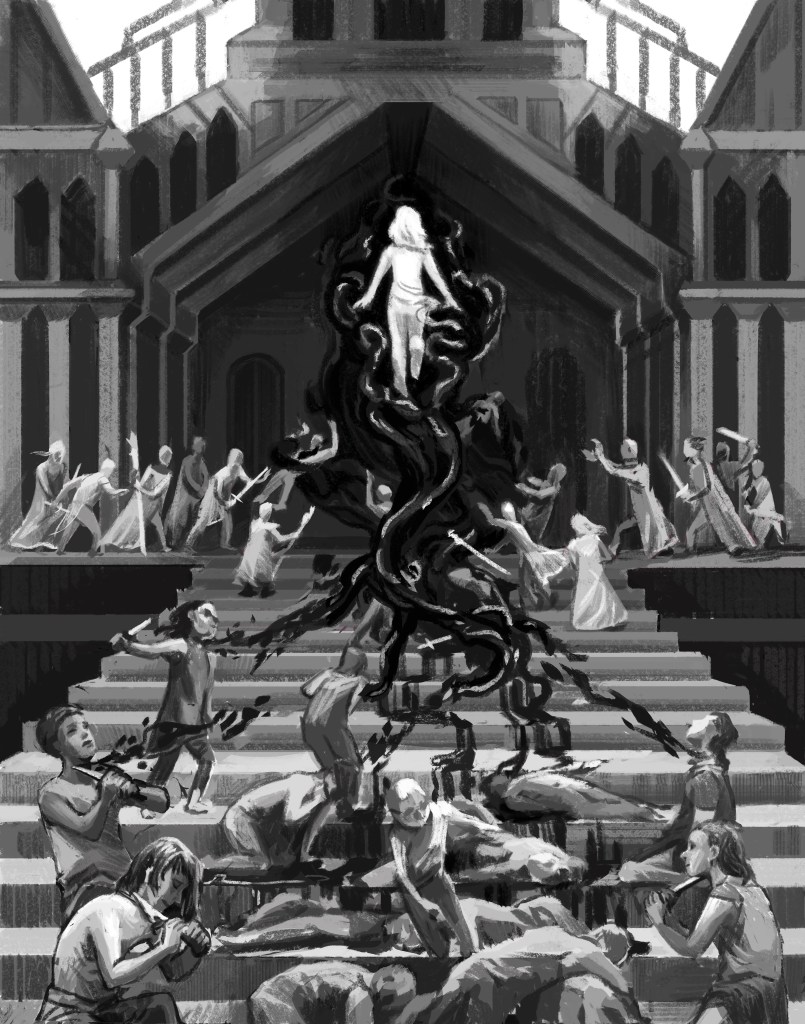

“The pointlessness of all the rebellions in El Dorado–the deliberate pointlessness–that was the point. Changing the world is vanity. The revolution must be subjective, or at least physical in the body, not physical in the world. That’s why Alice felt her body changing. Subjective transformation first, and the change in the world will follow. You can only change the world from the inside out. Those who would start by changing the outside world are starting all wrong.”

Alternatively, at a somewhat lower reading level, from Netflix’s Nimona:

“Ballister: No matter what we do, we can’t change the way people see us.

[Pause]

Nimona: You changed the way you see me.”

To be clear, that isn’t a criticism. Life’s most important lessons are often deceptively ubiquitous, and literature’s role is to affirm insights–it virtually never makes an insight that’s actually new. And Alice affirms this notion–that human power over the world originates within the self–beautifully, piecing it into a framework of interconnectedness not unlike the oneness and being you might encounter in the midst of an acid trip. This is intentional, of course: Alice’s dream-insights arise from the…unique qualities of her genetics, but she finds herself connected to individuals who became connected in this way, literally, from drug use. Why this is such a common experience with psychedelics in the real world is an interesting topic. I won’t address it here, but the assertion that said interconnectedness is a real thing that the drugs simply give access to is, at the very least, reasonable within the bounds of literature. Still, it’s on the threshold of where I think Alice stumbles.

As an affirmation of those theses in psychology and social connection, Alice does a fantastic job for as long as Alice’s experience is foggy enough to ward off the insufferable mosquitoes of material reality, the annoying inquiries of “yeah, but does it actually work like that?” Having written a whole novel manuscript with a plot predicated on a quantum-mechanical basis for sentience (and extinction), believe me, I relate to the challenge of making up believable science, but Alice’s invocation of the economic history of the Hoarder Wars, the lab and the social control schemes of El Dorado, the Mitochondrial Eve–one has to wonder if the coherence of the argument might have been improved with less scientismic dei ex machina.

I’m not entirely hostile to it, and I will readily admit that there are a lot of cool meta-dynamics within those details, but writing realistic but fantastical hard sciences is, well, hard. The inner workings of chaotic systems are stupendously difficult to discern; paraphrasing Lou Keep, it’s unclear whether there is anyone alive who really understands how “the economy” works. So when Alice postulates a delta within a single lifetime, from 1970 upstate New York to a post-apocalyptic-war clean slate in which there are two towns and a total population of ~300 people (and almost no one has any memory of the war, and also no meaningful technology has been lost, and actually significant technological strides have been made, etc.), I 100% understand it’s not the point, but the material details are distracting. I don’t think it’s entirely the text’s responsibility to provide those details, but it provides just enough that the HOW?! in the back of my head is deafening.

My feelings are even more mixed (though, to be clear, for the better) on Alice’s use of genetics. The book employs the Mitochondrial Eve, the matrilineal common ancestor of all living humans, as a symbol for the ebbing of possibilities and the cyclical repetition of human history. Putting aside the perhaps unnecessary paradox of those two concepts being symbolized by the same entity, I found myself a little distracted by the fact that that’s neither how genetics work nor how they are used. Said differently, I found the actual subject of genetics to be a poor substrate for what it felt like the book was trying to get at.

But there’s still something cool here: A prevailing theme in Alice is ancestral connection, which is experientially, psychologically, a very key part of what it means to be human. And I get it, literature can be what we want it to be, and there seems to be a want for that ancestral connection to be more than experience and psychology–the want is for it to be real, for it to be true. So Gautier asks: Why can’t it be chemical, embedded in our actual, physical DNA?

The answer: cryptography. Since, to the extent that environmental factors get encoded into our DNA, they are encoded many-to-one, you can’t decode them backwards without a key. The book clearly gets this at some level–much space is devoted to keys that would unlock this: the aforementioned psychedelics, an “elixir” brewed up by a young witch from medieval Germany whom Alice speaks to in dream space, a literal skeleton key that Alice finds early on. The symbol of a key allowing one to access the encoded past is absolutely there.

But it’s messy. The encoding is literal; the key is metaphorical. The Mitochondrial Eve, a temporally moving target (the common ancestor of all living humans changes depending on which humans are currently living) is framed as fundamental root potentiality and an inevitable return to “true alpha”. The environmental information encoded in DNA–in reality, stuff like “drank a bunch of lead before adolescence” or “was, by sheer happenstance, good at throwing things and lived in an environment where that was relevant to survival”–is so far from what ancestral memory actually means to us that these sections just fall a little flat. Though, reiterating, these are impressions and not a final reading–I would absolutely welcome discussion on this take.

Belatedly, I think another side of it is that the prose, which fits the buzzed out tranquility of the commune’s life excellently, is not a great match for technical description. Consider Alice’s conversation with Faunus, the director of the lab at the rival town of El Dorado:

“‘Or maybe,’ continued Faunus, ‘the cyborg approach, using artificial intelligence and robotics. Artificial intelligence will give you control alright, but it always tends toward total control, total surveillance. All freedom is lost. But now we’re getting back to the idea of the fascists, aren’t we? But the fascists, as I said, were rooted out. And robotics? Sure, you can make someone faster, stronger. But human nature? No, the cyborg approach–artificial intelligence and robotics won’t do.”

I’ll admit that Pan the Venture Capitalist is a symbol I have not entirely unpacked. But beyond his Greco-Roman cred, Faunus very much resembles a caricature that applies equally well to podcasting VCs and drunk hipsters at house parties: This is a guy, surrounded by people who think he’s a genius, who has absolutely no idea what he’s talking about. All of his thoughts and perceptions are organized into neat, macro-philosophical boxes, labeled things like “Fascism” or “Artificial Intelligence” while he leaves the messy details/comprehension to his employees and/or no one. I got the impression that this was at least partially unintended, largely because the tone (again, informal, full of imprecise commonplaces and memes) is kind of how Alice describes everything. In context, I got the impression Faunus was supposed to sound ambiguously villainous, walking through the twists and turns of his plan for social control, but the language isn’t quite right. Social control can be described from a wonk perspective (see Pigouvian taxes) or, more horrifyingly, from ideology (see Goebbels), but getting it in milquetoast party-chat over tea rather conveys the impression that none of the underlying machine actually works. I mean, perhaps this was intended: In the end, the lab fails to achieve its (or, discernibly, any) goal and gets a couple people killed. It’s a very digestible moral with regards to the desert of top-down social engineering. My skepticism is merely with respect to the highly dubious intentions behind it–intentions which would have carried more weight had they been better thought out (or rather, expressed in the language of those doing the thinking).

Despite the criticisms, I don’t mean all the harping to be much more than a warning sticker in aggregate. On the whole, I found Alice very much worth reading. Despite the simplicity of the prose, it was literarily very crunchy, and though I wrapped it up some weeks ago, I’m still thinking through it. Moreover, I’ll certainly be checking out more of Gautier’s work in the future. There’s something inspiring in this horribly modern era about his belief in human potential. The faespeak, for all its limitations, makes for good dreams.

Some notes:

- Those who read my work frequently probably already know this, but I want to be clear that my use of the term “meme” is academic here. I am referring to commonly-understood ideas and idea fragments, not to Advice Animals.

- Because the book is titled Alice and involves journeys into dreams and/or the subconscious, I would be remiss to not at least mention the potential for references to Carroll. I have not read Through the Looking Glass, so I don’t feel confident asserting anything in particular, but an allegory between the social control schemes of New Arcadia versus El Dorado and the opposition of the Red and White Queens does seem at least possible.