Realized it’s been 10 months since the last chapter of this story. Man, time really does fly, fun or no.

There was something that needed to be done. Devlin felt it, powerfully, desperately. Except for rescuing Orphelia, he was certain it was the most important task he had ever faced. And yet, somehow, despite the burning sense of urgency practically holding his eyes open as he rolled fitfully on his bunk in Brill’s infirmary, he had no idea what it was he had to do.

At least he could see now.

Since the Chateau de Marquains, the birds had returned in force. They were on and around him, rustling, flapping their dirty wings as he choked on the miasma that wafted off them. They would perch on his bare skin, place their beaks against his eyes and utter a hollow, rattling croak. It felt like encouragement. It felt like a threat. He wasn’t sure to what end. Their presence still stifled, anxiety like heavy mist. But unlike before, he could see. The feathers from their wingbeats fell beside him rather than clouding his vision. And unlike before, he could move. Rather than harry and hinder him, it was as if the birds attempted to lift him when he walked. He felt like he was floating, sometimes, each step not weightless but ineffably light.

He was still worried about Orphelia. Always worried about Orphelia. She came home concerned. Not concerned. Distressed. Not home. Brill’s infirmary–what was home, anymore? What could home ever be? None of that was important. It would all be okay if he could just complete this last task.

Devlin clutched his temples as he felt a wave of pinpricks in a line down the side of his skull. Slowly, the pain receded. […] For a moment, the birds were quiet.

Orphelia was safe, though, right? It wasn’t like Les Marquains could chase her all the way here. It seemed absurd that he would even want to.

No, Devlin thought, strangely assured of the notion: Les Marquains had no reason to pursue Orphelia. And the False God would have to be distracted: As they fled, the Saraa Sa’een had burst through the magically-reinforced walls of his chateau. Was Les Marquains even still alive? It was a useless question. It had nothing to do with Orphelia, with determining what it was that found her here. Whatever it was that scared her. The birds quietly muttered their approval. They knew he was right. They would help him protect Orphelia. But he would need to get up. He would need to go out and see what lurked in the Crossroads’ alleys. No, it was okay, he realized. The thing that kept him awake, the thing he needed to do: This would be the first step.

The birds fluttered up around him, lifting him from the cot, holding him steady as he crept to the curtain, across the apothecary shop floor. He lifted the deadbolt and slipped out the front door.

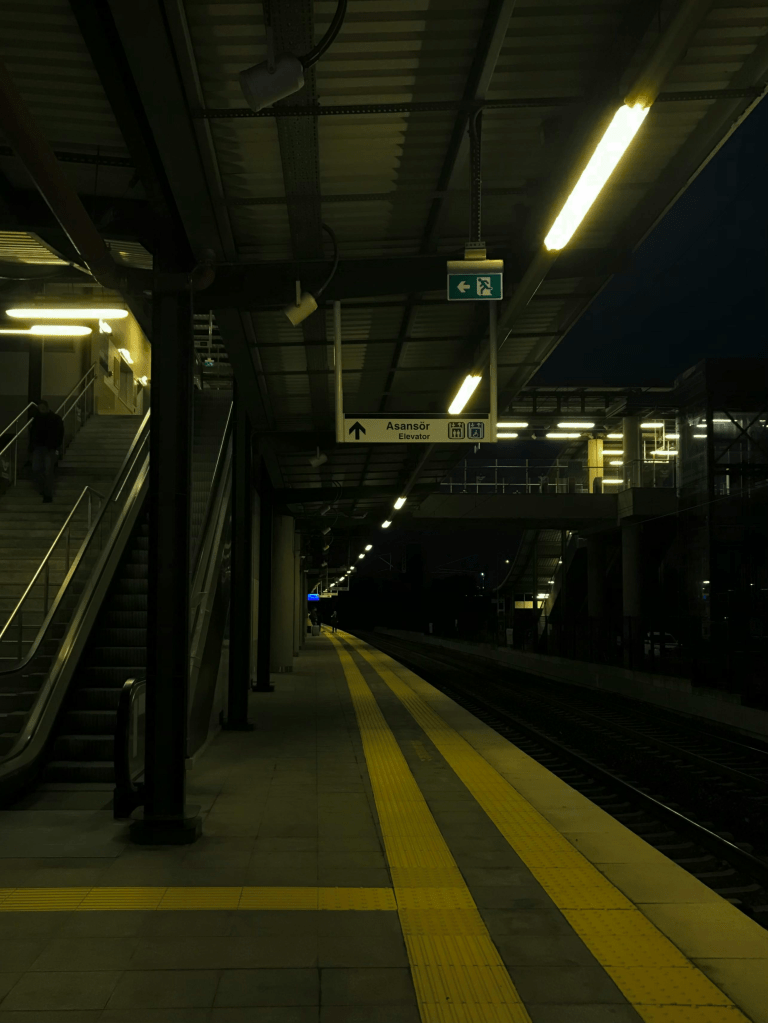

The birds hadn’t yet seen much of this Crossroads, Devlin thought, confined as he had been previously to Brill’s infirmary–and the alley across the street before that. This little patch of squandered potential sprung up in the ruins of Ulrich’s Bend, itself barely an outpost of the arrogant, long-ruined Kol. So close to what had once been the Blackwood–now open marsh at the outskirts of the Windwood. Though one had to admit the Bloodwood was a better name for it. A name befitting a substrate for the loathsome fungus of human tenacity, never bothered to pull its way upward, yet nigh unstoppable in its stubborn push forward.

Somewhere, secondarily, Devlin wondered how he knew these things, why he made these judgments. He didn’t remember learning any of it, but it had been some time since he had felt awake.

The streets were empty now, of course. The inn where Orphelia had been had locked its doors, all of the Crossroads’ late-night wanderers had settled for the night, at the inn, their homes, the posts at the thoroughfare intersections–in the case of the militia volunteers playing the role of night watchmen–and, for those vagrants too poor or too cheap for more sensible lodging, squirreled away in secluded alleys about the town, much as Devlin and Orphelia had been when they first came here.

But despite the quietude, the birds saw things, now that they were awake, now that they were helping. They fluttered about Captain al’Ver’s boat-wagon, tied outside Brill’s shop. They dared not land upon it. It was not theirs. But this place, this Crossroads, was no one’s. Between their domains. It was not her right to meddle here–which was why the birds merely watched–but it was not his either. Captain al’Ver gave up long ago. They all did. Why this sudden regret?

A wave of dissonance washed over Devlin, and the pinpricks in his temples flared again. Orphelia. Captain al’Ver was watching Orphelia. Because of his mistake. His own poison gift. The birds croaked menacingly, and somehow Devlin understood the implication: It was upon that observation that he became watched. And because he understood that connection, he was not afraid when he turned and saw the watcher, seated in the shadows beside the door of the inn. Beneath a wide-brimmed hat, eyes glinted orange in the light of the brazier down the street.

The old man rested a hand on the stock of a crossbow laid across his lap. He sat, but he was not inert, the weathered lines on his face showing no trace of fatigue. The scowl, the stare, the mechanical poise of his fingers–he saw through Devlin, and he judged. Devlin did not know what to say, but the birds spoke through him:

“I was betrayed first. What right do you have to intervene in my retribution?”

The corner of the old man’s mouth creased, and his knuckles whitened around the crossbow, but Devlin did not wait for his assent. He turned and walked away, toward the north end of town. The nature of Orphelia’s predicament was growing clearer, but there were other winds blowing about this place. The merchant of bespoke blights–this Marko–he would shortly have designs upon the Homunculus abomination. How could he not? But the birds could not guess what those designs would be, so maybe Devlin could find out?

The story the silver man–the abomination, the Homunculus– had told in the infirmary was not alarming to Devlin. It sounded foreboding, ominous. The awakening of the Night Sky sounded like a Very Important Change. Scary, in a far off sort of way–but also exciting? Hopeful? Like a promise of eventual relief. It was a strange way to feel about what Captain al’Ver said would be the end of the world, but Devlin had been in this haze, so tired for so long. He wanted it to end. He wanted it all to be what it had been before. But ending…the sickness, the transience, the sleeping through raspy coughs on boats, in alleys, on infirmary cots–ending that was the first step, right?

The birds’ startled croaks wrenched his thoughts away from that confusion, drawing his gaze upwards. Devlin’s eye caught Ty Ehsam, perched on the roof of Gene’s smithy.

Rogue, the birds croaked. Wayward child. Did the crawling worm not grasp the opportunity before them?

For just a moment, Devlin wondered how it was that the birds’ tittering placed these thoughts into his mind. As if they were his.

But he had a task he had to complete. Time was of the essence. He continued on toward Marko’s.

***

Ty shivered as Devlin looked up suddenly, directly at him, one eye obscured by his ragged hood, the other clearly–almost ethereally–illuminated, piercing, frozen grey in the faint torchlight. It was by no means alarming that Devlin noticed him, of course. They had come to town together. To the extent that the boy had been paying attention, he would have known that Ty was keeping to the rooftops in this general area of town. Still, the interaction had been uncanny.

“Well, I would say we’ve been clocked.”

The whisper came from Ty’s mouth, but the words were certainly not his, prompted instead by scarcely detectable pulses of mana running through the threads sewn into his head and neck.

“What do you mean?” Ty asked under his breath. “The boy knew we were here.”

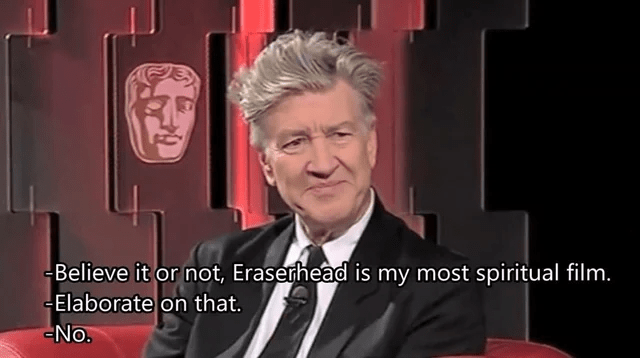

“The boy?” the Dragon replied in Ty’s voice. “You gods forsaken idiot, you think that what just saw us–and I mean us–was a boy?”

Ty did not respond. The Dragon’s abuse was more or less a constant when the False God spoke to him, and he saw little point in engaging with it. He followed Devlin as the boy–or whatever the Dragon thought he was–continued up the street, stumbling and meandering in much the same way he had ever since leaving the Chateau de Marquains.

“I can forgive a simpleton like you for not sensing the mana. It’s a subtle flavor, and his sister is much, much louder with her magical pollution. But have you really not noticed the way he hides his hand from al’Ver?”

Ty had not. He considered it for a moment.

“Is he hiding his ring?” he asked.

“A lovely guess. It is better to be stupid than stupid and blind, I suppose. What can you tell me about this ring?” Ty shrugged.

“Cheap,” he said. “Looks like dirty iron. Grooves cut into the flat on one side. Are those supposed to mean something?”

“It shocks me that you’re even intelligible, let alone literate,” the Dragon sneered. “Grooves? Mean ‘something’? That is a bird’s footprint, you dunce.”

“You say that as if it’s a crest I should know.”

“Only because it is. That is the crest of the Strange Bird.”

Ty glanced again at the street. Devlin had disappeared into the shadows, and all was once again silent and empty.

“Never heard of them,” he said, leaning back against Gene’s chimney. “Another new False God?”

“My disgust can scarcely be vocalized,” came the Dragon’s surprisingly calm reply. “They’re almost childlike, your priors. Raised in a world of bad replicas, you are unable to recognize the real thing. Even when you run right into two of them. But I suppose the Feathermen disbanded decades before you were born, and why would you have learned their master’s sobriquet? It was buried on purpose, precisely so that fools like you would forget it.”

“Well, sorry for the foolishness, but I don’t follow,” Ty whispered. “The ring is magic, I assume? And it’s linked to this Strange Bird–so what?”

“So she saw us. And you’re just going to let him dance off to his business in the dead of night? Get up and follow him, you idiot!”

Ty sighed, carefully creeping to the edge of Gene’s roof. He leaped over the small alley between the smithy and the potter’s workshop next door, proceeding to make his way after Devlin as stealthily as he could.

“She saw us?” he asked between measured exhalations. “Who is she, exactly?”

“The Strange Bird,” the Dragon replied. “The One-Eyed Crow, the Lark in the Burning Tree, et cetera. And the kid’s been traveling with you all this time: She’s seen everything there is to see about you. I am more vexed that she saw me.”

Ty frowned, annoyed as much by the Dragon’s vagaries as the thinning of available rooftop routes. He carefully lowered himself to the street beside a vegetable garden wedged randomly amidst the tradesman’s corridor and took to the street, beginning to push out a field of mana, a subtle, vacuous delusion, the technique Naples called “shadow walking”.

“So what does it mean?” he muttered, quickening his pace as Devlin swayed toward the square up ahead.

“I shan’t waste any more pearls on you,” came the flat reply. “Find a codex if you’re curious. Suffice it to say that we should underestimate neither the number of parties interested in our Homunculus, nor their level of interest. Now keep following the damn boy. The more I can learn about her angle, the better.”

Ty’s motivation to carry out the Dragon’s reconnaissance was waning, but he really did not like the notion the False God seemed to be reading from the boy’s behavior. A fourteen-year-old boy being controlled by a mage–let alone one that could intimidate a mass-murderer like the Dragon? It was just…grim. Both Devlin and his sister had had a truly rough go of it, and though Ty had his frustrations with Orphelia’s relentless troublemaking, he couldn’t help but pity them. And he was left to wonder whether the boy’s ring was a problem he might be able to address. The Dragon didn’t seem to think there was any such opportunity, but Ty was also fairly certain the Dragon didn’t give a damn about the boy’s welfare.

For a moment, Devlin disappeared from view, rounding the corner onto the north square. Ty lingered there, peering out at the surprisingly well-lit space. To his surprise, Devlin had stopped scarcely fifteen feet beyond the turn, staring straight ahead. The benches, fountain, and walkways at the center of the square fell well within the torchlight, but Ty couldn’t make out anything there that might have given Devlin pause. He noticed it only because Devlin’s attention prompted him to keep looking, but there, under an awning at the opposite end of the square, Ty caught movement. Smoke. No–vapor.

The shadows behind the trail of steam stood and approached the boy.

“Devlin?” Bleeding Wolf rumbled, stepping into the light, pensively balancing a steaming wooden cup between his fingers. “What are you doing out at this hour?”

“Uhm…”

Ty could not understand Devlin’s response, barely a murmur as the boy swayed, hands balled up inside his sleeves. Apparently, Bleeding Wolf didn’t catch it either. The concern on the beastman’s face deepened.

“Let’s get you back to Brill’s. Maybe they’ll have somethin’ for the sleepwalkin’.”

Ty ducked quickly back around the corner, into an alley where he used a barrel as a makeshift step ladder back to the rooftops. He waited there for the next few minutes as Bleeding Wolf ushered Devlin past, back to bed, seemingly oblivious to the eldritch presence Ty had seen behind the boy’s eyes only moments ago.

“Did you see it?” the Dragon whispered once the two were out of sight. “He hid the ring from the beastman as well. Al’Ver is obvious, but why would she consider your ‘Bleeding Wolf’ a threat?” Ty paused.

“A threat to what?” he asked.

“Finally. A pertinent question. Alas, the boy retreated, so I don’t imagine we can be sure. Still, he was approaching…Marko’s office, was he not?”

***

“Here’s the plan,” Marko announced to his empty theater, no-nonsense, motivational-like, the type of confidence that ought to inject some energy into his thinking. Except he didn’t have the plan. He sighed, grumbling a half-hearted string of curses.

The pieces, then. Atra wanted to fight the Blaze, for whatever shell-forsaken reason. The Blaze wanted the Keystone. Unclear if he wanted the construct. He would if he weren’t an idiot, but… And the construct, this “Monk”, wants to…bring the Blaze to the site of the Night Sky’s awakening? What?

Marko glanced out at the torchlit shadows beyond the stage where he stood. He fiddled with his crossbow, concerned that he might not be alone but self aware enough to know that he was always thus concerned, that there was no signal whatsoever in his worry. He jumped down from the stage, landing hard, his knees just no flexing with the impact the way they used to, and he checked his wards and traps:

The unobtrusive strip of strange metal at the doorway–the same metal as one of the seven rings he wore–which dissuaded anyone from entering without his approval, still in place and undamaged, unlike the rest of his doorframe; the elongated stone brazier at the edge of the stage–a creation of Holme’s Sculptor–which burned without fuel and grew much brighter in the presence of violent intent, still alight with its normal, orange hue; the windows, all completely ordinarily shuttered but affixed with small parchment tags fastening the shutters to the sill such that they would tear if a window were opened–and which would instantly reduce the temperature in the vicinity dangerously below freezing upon tearing; and, of course, the trap door beneath the rug on the stage, locked both conventionally and with a magical device operated by his pendant which would, by default, redirect any harm done to the device, the door, or the room beneath it back at whoever was attempting to smash their way in. Everything was still in place, in working order, and crucially, only Marko knew how it all worked.

Back in the old days, it was once every couple years a scav would try him. Now no one had bothered him in a decade, excepting the Ben Gan Shui’s centipedal envoy smashing through his door the other week. But he tried not to let that affect his paranoia. This was a dangerous fuckin’ line of work, and being on the backlines of the scav trade really wasn’t any safer. His little stronghold wasn’t impregnable, though even the envoy probably wouldn’t have made it past the lock–and none of this shit seemed to work on Lan al’Ver, but it was still better protected than the vast majority of scav marks.

Marko heaved himself back onto the stage, his checks, his thrice-daily ritual completed. The pieces again:

If Monk wanted to get someplace else and bring the Blaze there, that gave Atra her stupid battlefield, right? So she could get herself killed, the Blaze would get his Keystone, and the threat to the Crossroads would be gone. With the threat–and Atra–gone, the militia would go, and Marko could find some means to wrench his mercantile autonomy back from the mayor.

What about that loose end, then? Mayor Bergen probably wouldn’t care about Monk’s prophecy, and who knew how much he cared about Atra’s death wish? He would probably want to ship Monk and Ehsam up north. Marko had to admit the simplicity was appealing, but Atra would certainly meddle. In the end, he neither trusted her, nor was he willing to put his neck on the line to give the mayor an unmitigated win–the mayor was his enemy too, after all.

“Here’s the plan,” he said again. “We got the research angle, see if I can dig up any scraps of wisdom I might’ve picked up from the Alchemist’s fanboys over the last few decades. Need to figure out where Monk needs to go. Hell, maybe the clockwork piece of shit will help me.

“Then the action. Gotta–” He stopped cold as the stone brazier flared up.

It was for just an instant that the flames sputtered higher, just a quick flash of light that brushed the dark corners of the stage before dying back to dim candlelight. Could’ve been a fluke. Something outside, whatever malice woke it up either phantom or just gone now. Or maybe Atra’s little spy tripped one of his wires.

“Don’t fuckin’ worry,” Marko muttered. “You’ll be in on it. Now fuck off.”

It was the truth, sort of. If everything worked out, Atra would get what she wanted, far away from here, at maximal cost to the Bergen boy’s stupid militia. But she couldn’t know in advance. He needed her to react hastily, to be taken by surprise. He needed to be driving this cart.

But whether or not his invective had been received, there was, of course, no response.