This keeps coming up in my writing for some reason. The first piece is an excerpt from a novel I wrote some time ago. The second is a story I wrote more recently, featuring the Smile.

Espereza’s Riddle

“Let’s get to know each other, Samuel.”

“What the fuck is that supposed to mean?” Samuel yelled. Espereza grabbed him by the shoulder and slammed him into the rock.

“Tell me, Samuel,” he whispered, the syllables rolling out wet and reptilian. “Have you thought about my riddle?” Samuel scowled.

“Your riddle?”

“Yes. A labyrinth. Two doors. Two guards. Do you recall?” Samuel sighed with disgust.

“Sure,” Samuel said. “You ask each guard which door the other would recommend to get you out alive. Their answers will be the same. You take the other door.”

“Really?” Espereza asked, his grip on Samuel’s shoulder still firm. “I think a fair amount of the time, their answers will be different.”

“No,” Samuel said, annoyance seeping in over his fear for his life. “You said one always tells the truth, the other always lies–”

“I didn’t say that.”

“What?” Samuel asked.

“I didn’t say that the other always lies.” Samuel stared into the man’s black eyes for about ten seconds.

“You can’t solve the riddle if one of them only sometimes lies!” he said, finally.

“I know,” Espereza replied. “Isn’t life just awful that way?”

The Smile’s Riddle

Care to join me in a game of riddles, my dear?

Suppose you find yourself in a passage you must escape. Before you are two sentinels. One tells only truth, the other only lies.

“I am Truth,” says the first.

“I am Truth,” says the second.

Behind them are two doors.

“This first door leads to terrible agony,” says the first sentinel.

“This second door leads to terrible agony,” says the second.

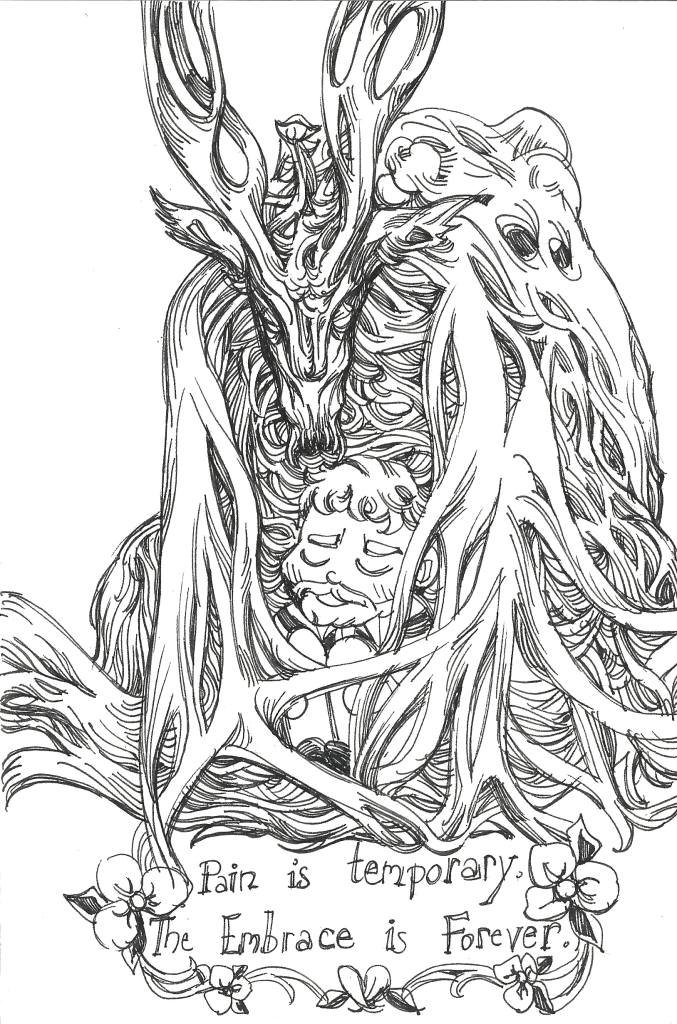

Your companion, thinking he has seen past the riddle, enters the first door. You, under the same impression, enter the second. Some time later, your companion exits the passage with memories of torture, violation, and such atrocities visited upon him that he would sooner drown in an ocean of drink than recall. In the same time, you exit with those same memories.

So who lies? Is it the first sentinel? Is it the second? Or is it me?

What, for that matter, is a lie? In my homeland, it was a mismatch, words or images set against a reality that rejects them. Our dead queen, immortal in the dark of her ziggurat, bade us–myself, your precious Rom, all of her shadowmen–bade us go and tell lies of fear and unrest to her people, our enemies, anyone who would listen, really. It was all such a waste. Right there, all the potential in the world, squandered for a bad lie told by a bad liar.

The thing about a trick of the light is that it makes the trickster apparent. Back to the riddle: There is no trick, no obvious mismatch of words to reality, but that’s because you have no knowledge of reality. No, all you have is memories, and they lie more fluently than any sentinel. If you believe them, in fact, there is no lie. Thus spoke the Man of the Clouds, the greatest leader I ever knew.

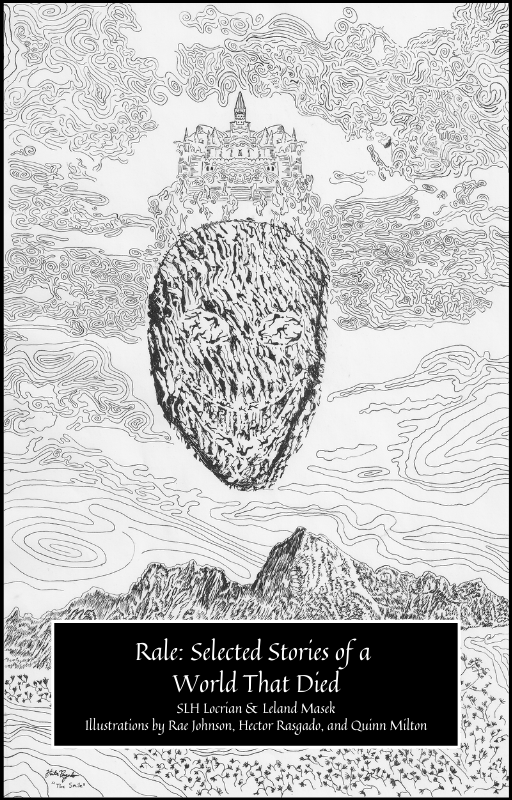

He proved it, too. You see, all we ever needed to do to throw off the queen’s claim–that she was immortal, that she was Death, whom we all must serve–was to stop believing the lie. He led us from that pit, into the sky, and the eternality of Khet just fell from reality, as dew from shuddering grass. It is not even that his City in the Clouds was any different–just images and sensations and words and dreams, sculpted of vapor and bequeathed to any who would believe his lie instead. And of course we believed it. It was idyllic paradise over dronehood before unending Death. No, the turning point was what came next.

One day, the travails of my past life well and truly recovered from, I stood at the edge of that City in the Clouds and looked down at the great sea we appeared to pass over, and a single, ruinous thought thrust into my brain: I didn’t believe it. Do you know why? Do you know what I saw, down there in those depths? It was nothing. Nothing below, in those waves; nothing in sight, save for our city; nothing real beside peace, goodwill, and the serene ephemerality of clouds. It was a pretty, elegant lie, but elegance is only of use against a particular problem, and my problem was not particular. It was everything. All of reality–the grim, beautiful, violent reality the Man of the Clouds had omitted from his paradise–I knew to be down there in that roiling Deep.

So I descended–and those who knew as I did followed–to go and imbibe the horrors and agonies of life, to create a new lie, a grand story of this whole, glorious, accursed world. With what we learned, we would build a new stairway to the sky, a stairway of earth and blood, and we would prove the primacy of our lie, just as the Man of the Clouds proved his.

Which brings us, as ever, back to the riddle. Did your memories lie? Did the sentinels speak falsehood? Or within those passages was there merely life, just as without, with its rocks and thorns and fears and pains? And if everything was true, am I the liar for posing the question?

“I am Truth,” says the first sentinel.

“I am Truth,” says the second.

And, of course, I am Truth as well.