I lied a little in my last post. I was not, at the time, working on a Bloodborne *article*. Rather, it was a lecture that I have since delivered, and I am now working on transcribing it to a format more suitable to this blog. For now, have something completely unrelated to anything I’ve posted about on this blog up until now.

In the beginning, in a meaningless place, at a meaningless time, the universe began, and where all was not, all rapidly became. Countless bodies, infinitesimal in size, fled that place. Many bound together and ignited, filling the darkness with light. Others swarmed to the pyres of their brethren, filling the void with ground to be stood upon.

But after the exodus, in that meaningless, empty place, given meaning and space by the light and matter without, there remained a tiny, black droplet of something. Perhaps it was the last trace of the void, left behind as a reminder of all that would ever not be. Perhaps it was a tear of regret, shed for the infinite potential that died to birth everything’s actuality. Whatever it was, though, it could only watch, its oily surface reflecting the whole of the universe around it. And so it was, for innumerable millennia: The universe turned, and the black droplet at its center watched.

There came a moment, though, when this changed. It was nothing precipitous. Rather, it was a slow sweep, a foul stellar wind that made its way across existence, brushing everything but truly touching nothing. Nothing…except the black droplet. At this moment, it began to roil, its perfect surface marred and twisted, and, rapidly, it swelled, to a globule, a morass, a fetid, writhing planet no longer confined to regret and observe, now able to reach out and to touch. For another million years, the primordial darkness writhed, and, slowly, it separated into two dark souls.

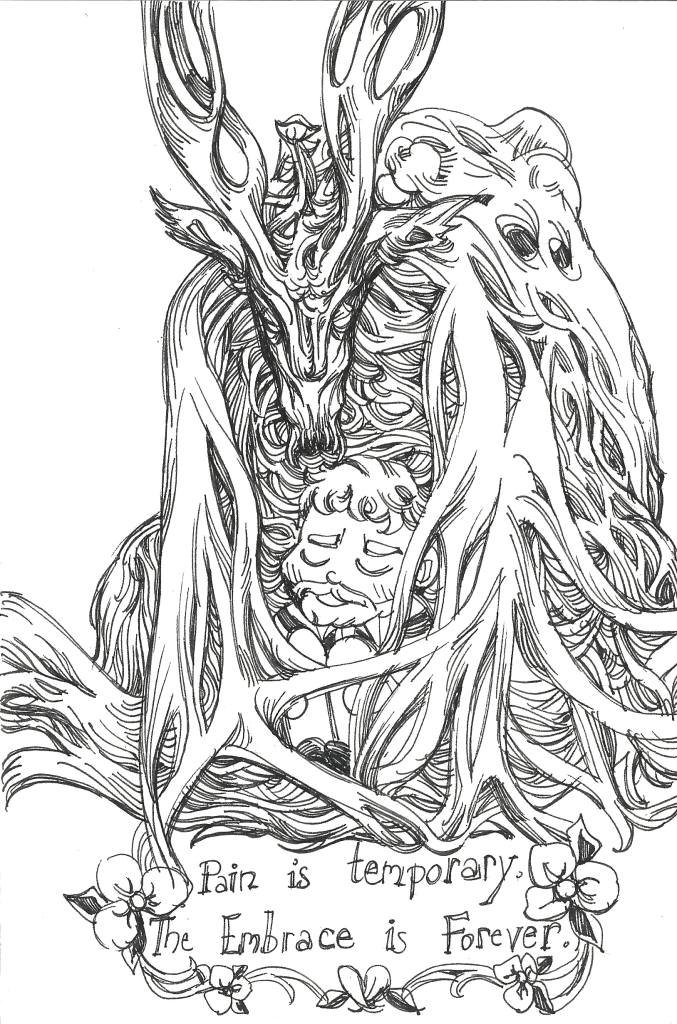

The first was the Dreamer, a being of pure consciousness, who had once reflected the birth of the universe and whose improvisations of that birth now swam beneath the viscous seas of its planet. It had no true shape, so it instead cloaked its shadow in the cold brilliance of a thousand suns and made a heaven for itself at the center of the planet, caged within the darkness of its sister’s coils.

The sister was the second, a Sleeper, a body by which to bear and make manifest the chaos of its brother’s mind. And just as the chaos of the Dreamer’s thoughts encompassed every notion the universe had yet known, the chaos of the Sleeper’s presence consumed all that contacted it. Planets bent and were devoured, the light of stars was swallowed, masticated by her entropic gaze; even her name was poison to order: The very syllables that formed it would implode its utterer into a singularity, and the only mind that could bear its knowledge was the Dreamer’s.

The Dreamer also had a name, though it would yet be billions of years before a human heard its sound or sign.

The Elders, as they called themselves, hated the reality that surrounded them. They hated its order, its belonging, its iron actuality. The Sleeper channeled this hate into destruction, and for a thousand years, the universe felt her wrath, and countless galaxies fell into her churning darkness. Ultimately, though, it was the Dreamer that calmed her, for his hatred had pulled him in a very different direction.

Hatred, the desire to destroy, is not a particularly complex feeling, but with even such a simple desire, outcomes are never sure. In hatred’s case, they need not even be destructive. Rather, inherent in the desire to destroy is a preference for an alternative, which means that unless the alternative is explicitly void, it may be resolved by creation, as well as destruction.

The Dreamer hated reality, yes, but he did not long for nothingness. He was a child of the infinite–his enemies, the objects of his hatred, were the limits of reality, not reality itself. So rather than lash out against the universe–as the Sleeper had, with world-breaking fang and sun-swallowing night–he simply questioned. He dreamed a thousand questions for his sister’s millennium of destruction, and the questions took shape from her flesh. First among these new Elders was the first among questions: Why.

Why was a creator, a conduit by which his father’s potentialities took shape, but, unlike his predecessors, he was not possessed by the hatred that birthed him. At first, he took after his mother’s example: destruction. His first creations were tempestuous, chaotic, themselves destructive: Slithering storms that rained leeches onto the surface of the Elder planet; great writhing masses of maws and arms that could devour entire stars, weapons whose very presence could distort the laws of causality. In their way, they were brilliant, fantastic, awesome even. But they did not satisfy Why, for he did not hate the things they destroyed.

So he diverged.

He built two creatures, towering men of stone and metal. Like his previous creations, they were capable of great force, but they were stable. They could process the reality that flowed around them, and they could manipulate its currents. Above all, they could choose.

One was black and mirrored, just like the droplet of potential that had spawned the Elders, a glass to reflect the whole universe once more, and an eye from within to watch it.

The other was clad in gold and silver and pure light, its radiance reaching out to the blackest reaches of space, even from its darkest center.

The two were called El and See, and they were not Elders, for they had passed beyond their creator’s heritage of chaos and hatred. They were creators themselves, and thus Why named their species: the Architects.

Though Why’s nascence had calmed the Sleeper’s rage–for her son had been a potent weapon in her war against what was–the creation of the Architects stirred her from her slumber once more. These newcomers were not alternatives to the universe: They were developments of it. Their shapes were still, ordered, thoughtful, able to exist alongside what was, without the existential agony that plagued the Elders. Certainty flared within the Dreamer’s mind: The question “Why” had been a mistake.

But Why knew the doom he would bring himself. He knew that his creations were heresy, so long before the Sleeper awoke to devour her prodigal child, he fled with the Architects, and the three hid themselves deep within the blackness of space.

In a desolate place, far from the light of any star, the Architects multiplied. El and See forged brothers and sisters, specialized beings of motion and stillness, of joy and sadness, and, finally, of life and death. These last two, the Architects Vie and En, captured Why’s attention, for life and death seemed so different for his metal children. The Architects were creatures of perfect consequence: Life for them was elegant, axiomatic, and death was predictable, a simple end to the functioning of their working parts. For Why, these were different. Despite his relentless questioning, he still could not fathom the depths of his physiology, so he knew not why he was alive, nor why that state should ever cease to be. And since he understood neither what lay before or beyond–these truths, if they were truths at all, were understood only by the Dreamer–how could he understand what lay between?

It was El who supplied the answer: If thinking life could be formed from a union of causality with the Elder’s own flesh, it would provide him the perspective he sought.

The two of them devised a calculation grander in scale than anything Why had ever imagined, and they reverse engineered the impossible specificity of its initial conditions, and they searched and searched, until they found two candidates for their experiment. They began with the first: A small system of newly formed planets orbiting a yellow sun. And on the surface of the third planet, See placed a tiny sample: the eye of his Elder creator. Then, they all waited, in eager anticipation.